Image Credits & Additional References

NIJINOMATSUBARA FOREST

Map of Nijinomatsubara;

courtesy of author.

courtesy of author.

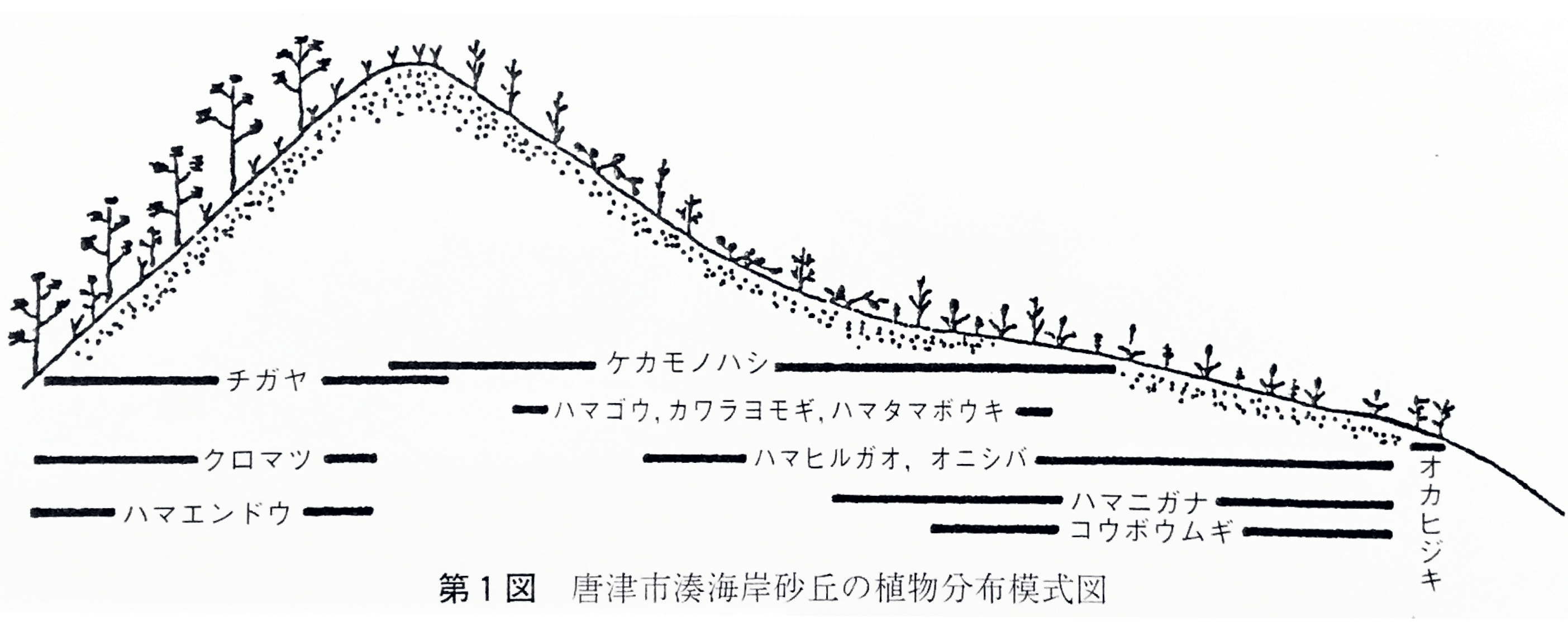

川浪, 誠. 2000. “II. 虹ノ松原の植物相”. 日砂丘誌 47 (0918-5623): 136–37.

長谷川, 雪塘. n.d. 唐津城下絵図. Japanese painting. Karatsu: Karatsu City Hall. Reproduced with permission.

木崎, 攸軒盛標. 1786. 江猪漁事. Drawing. Saga: Saga Prefecture Museum. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph of black pine sapling growing on the beach; photograph by the author.

Photograph of black pine interior of managed forest; photograph by author.

Handwriting by local historian Yo Yamada; photograph by author.

Wilson, Wilson. Pinus Thunbergii

Japan [Title from Recto of Mount.], 1914. Courtesy of The Arnold Arboretum Library at Harvard University.

Japan [Title from Recto of Mount.], 1914. Courtesy of The Arnold Arboretum Library at Harvard University.

Wilson, Wilson. Japan – Hondo

[Title from Recto of Mount.], 1914. Courtesy of The Arnold Arboretum Library at Harvard University.

[Title from Recto of Mount.], 1914. Courtesy of The Arnold Arboretum Library at Harvard University.

An old-growth portion of the black pine forest; photograph by author.

Sawyer Beetle, male adult; dorsal image view, abaxial. Steven Valley, Oregon Department of Agriculture, bugwood.org, UGA. Creative Commons Attribution, Non-commerical 3.0 licence.

Fieldwork archive and tools; photograph by author.

Capturing the emergence of a mushroom; photograph by author.

Hatsusaburo, Yoshida, 1933. 唐津市鳥瞰図(裏)松浦潟名勝案内. Drawing. Saga: Saga Prefecture Library Database. Reproduced with permission.

Two of the most notorious black pines; photograph by author.

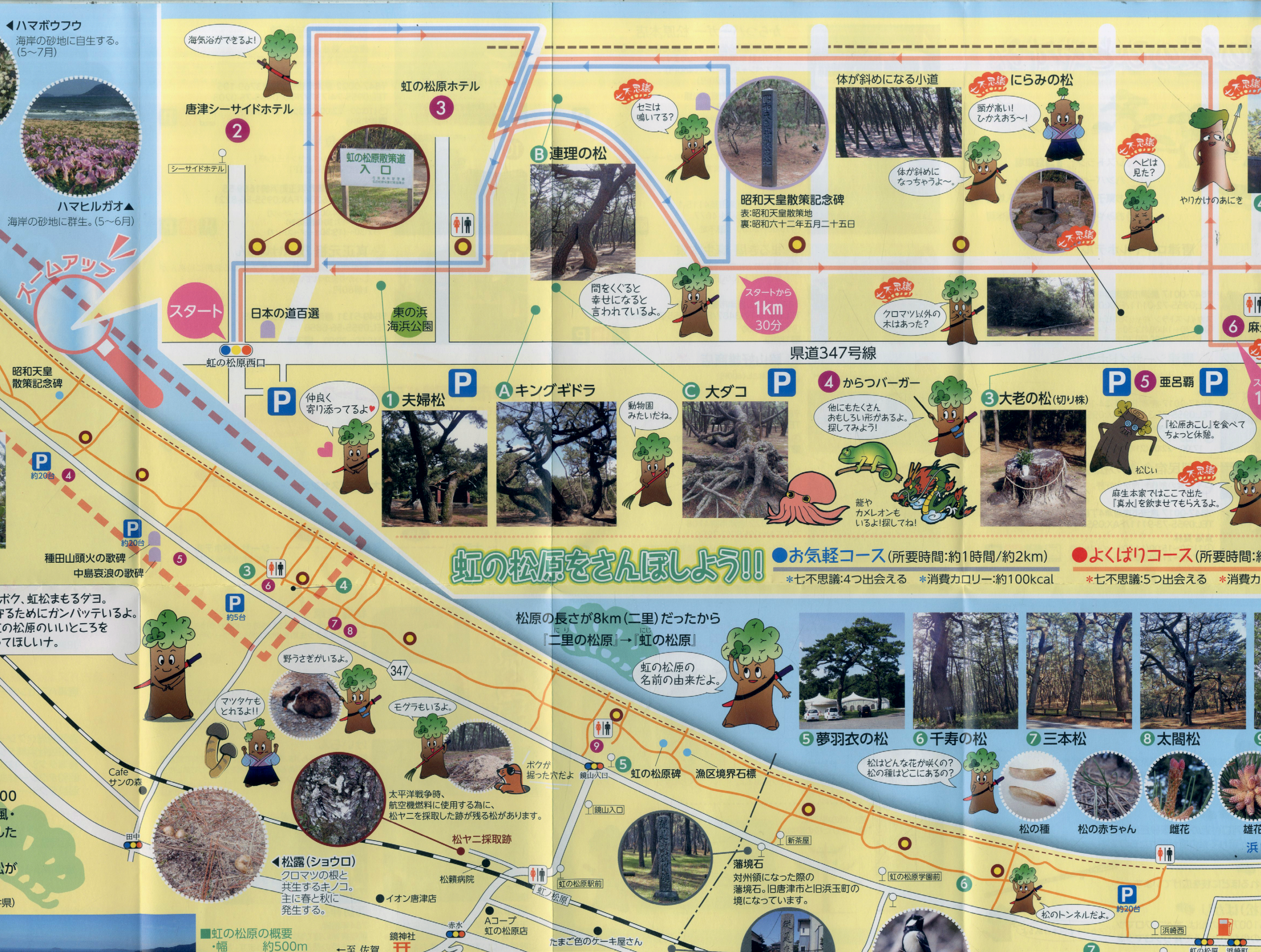

NPO KANNE, Tourist Information Map for Recreational Forest, in Business Report on the 2018 Fiscal Year [in Japanese], 2019. Reproduced with permission.

Fieldwork studies. These drawings use a grid transect to try and determine how many mushrooms emerge in one day, in two square metres. 8–9 May 2019, by author.

Fieldwork. Measuring the height of mushroom emergence; photograph by author.

Historic photographs showing the drama under the black pines and the effectiveness of the forest as a novel tourist destination. Private collection.

The view of Nijinomatsubara from Mount Kagamiyama; photograph by author.

The not-for-profit “KANNE” organizes community clean up efforts; photograph

by author.

by author.

Additional References

Peter Galison, “Specific Theory,” Critical Inquiry 30.2 (2004): 379–83.

Y. Mamiya, “History of Pine Wilt Disease in Japan,” Journal of Nematology 20.2 (1988): 219–26.

Peter Galison, “Specific Theory,” Critical Inquiry 30.2 (2004): 379–83.

Y. Mamiya, “History of Pine Wilt Disease in Japan,” Journal of Nematology 20.2 (1988): 219–26.

MAULE RIVER

Map of Constitución; courtesy

of author.

of author.

This map was commissioned by the grosvenor Jose Manso de Velasco, entitled: “El Plano de la Villa de Talca, Parte del Maule,” 1742. Reproduced from Jorge Núñez Pinto, Cartografia Histórìca de la Región del Maule. Talca: Fondo nacional de Desarrollo Cultural y Las Artes Fondart Regional, 2008. Page 32.

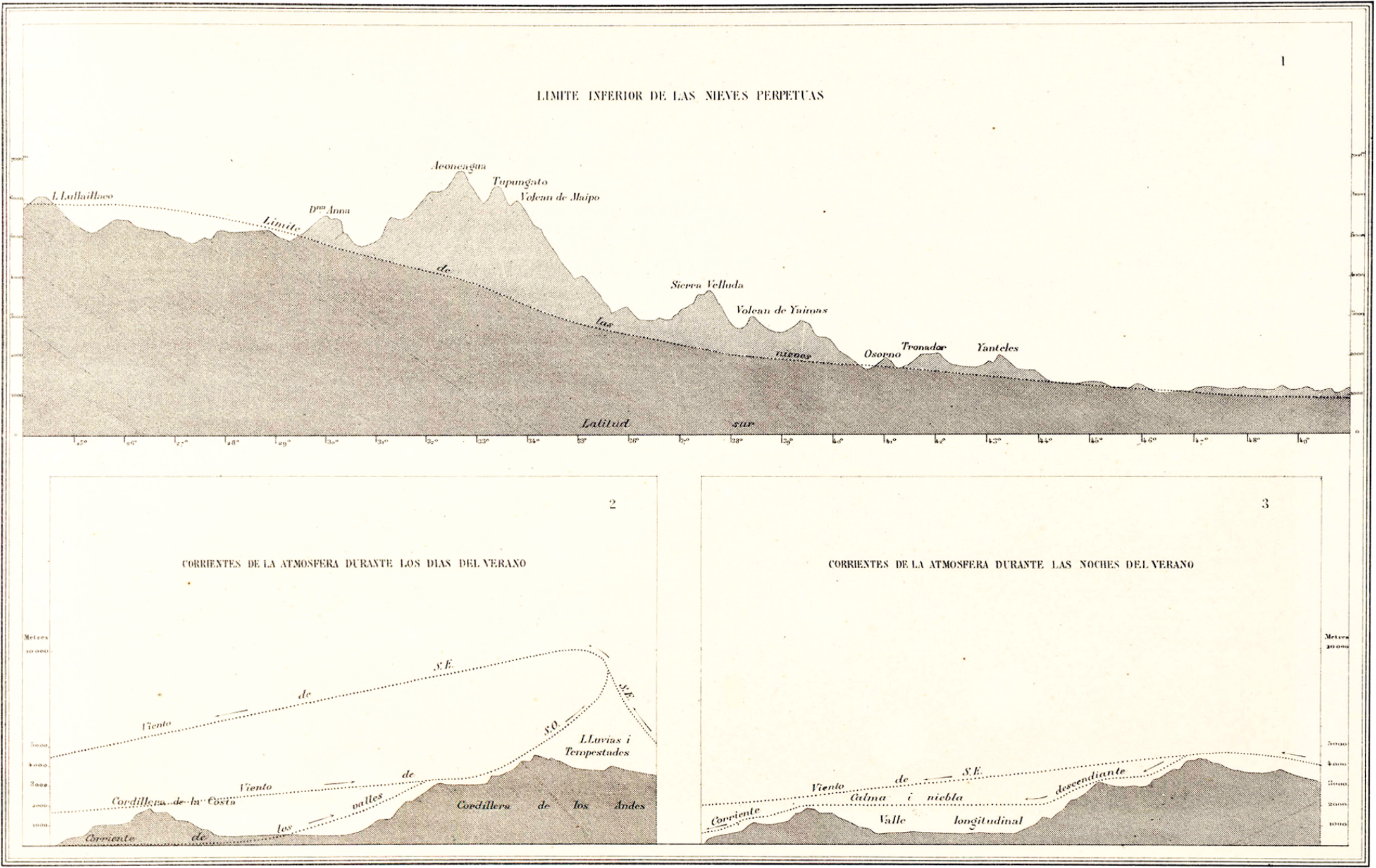

Aimé Pissis, Atlas de la geografía física de la República de Chile. Paris: Instituto Geográfico de Paris. Ch. Delagrave, editor de la Sociedad Geográfica, 1875. Reproduced with permission courtesy of Harvard University Map Library.

View of Constitución, with Isla Orrego and Maule River, Constitución, Domingo Ulloa, between 1950 and 1960. Biblioteca Nacionalo Digital de Chile. Reproduced with permission.

Fieldwork. Tracing the edge of pulp production outside Aruno processing plant in Constitución; photograph by author.

Photograph of Maule River from Kayak; by author.

Images of research. Reproduced with gratitude to Harvard Botany Library and Archive for use of their resources, including research in the Economic Botany Library of Oakes Ames, 2019; photograph by author.

Series of portraits of Violetta Parra with her guitar, circa 1954. Courtesy of Fundación Violeta Parra y Museo Violeta Parra, Santiago de Chile.

Talking with Bernardo Reyes in his garden in Santiago; photograph by author.

Sunset at the campgrounds along the Maule River; photograph by author.

Aerial view of the coastline of Chile, the white puffs are forest fires. Image courtesy Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Land Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC. earthobser-vatory.nasa.gov/images/2205/fires-in-chile. Public Domain.

The black sand beaches

along the coast of Constitución; photograph by author.

along the coast of Constitución; photograph by author.

Black pine saplings in production at Arunco nursery; photograph by author.

This photograph is part of a unique edited compilation that is renowned for exposing some of the plantations overtaking the forests of Chile and the impact that human action has had on them, region by region. Reproduced from Adriana J. Hoffmann and Defensores del Bosque Chileno (eds.), La tragedia del bosque chileno. Santiago de Chile: Defensores del Bosque Chileno, 1998.

Fieldwork. Appreciating spontaneous plants; photograph by author.

A team of kayakers from the film Rio Sagrado, which follows a 200 kilometer kayak descent along the San Pedro (Wazalafken) river, from its headwaters to the ocean, as a form of protest towards damming the river. Special thanks to Patrick Lynch, one of the kayaking activists in the image. Photograph by Carlos Lastra, 2016.

Fieldwork. Sharing edible plants foraged near a restaurant; photograph by author.

Additional References

Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia.

New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Vandana Shiva and Wendell Berry, The Vandana Shiva Reader (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia.

New York: Basic Books, 2001.

Vandana Shiva and Wendell Berry, The Vandana Shiva Reader (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2014).

NIUGTAQ VILLAGE

Map of Niuqtag Village; courtesy

of author.

of author.

“Another view of Jimmy Tom’s house, Newtok,” 1974. Photograph courtesy of Ernie Tyler from Ramona/California, USA; image via Wikimedia Commons.

A view of Niuqtag Village

from the air in. Reprinted with permission from Anchorage Daily News (ADN). Photograph by Marc Lester, 2019; reproduced with permission.

from the air in. Reprinted with permission from Anchorage Daily News (ADN). Photograph by Marc Lester, 2019; reproduced with permission.

Images of this kind began to emerge with concern of melting permafrost. Photo by NASA, taken on 12 January 2011. Courtesy of NASA/GSFC/Jeff Schmaltz/MODIS Land Rapid Response Team. Public Domain, anl.gov/article/thawing-tundra-a-new-climate-threat.

Photograph by Katie Orlinsky of melting ground in Newtok, 2019. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph by Alex Harris of swimming along the Niglick River, 1977. Reproduced with permission.

Leaves of dried labrador tea; photograph by author.

Betty Tom demonstrating how baskets are woven in Newtok, 1974. Photograph by Ernie Tyler from Ramona/California, USA; image via Wikimedia Commons.

Cancelled check in the amount of US$7.2 million, for the purchase of Alaska, issued 1 August 1868. Records of the Accounting Officers of the Department of the Treasury; Record Group 217; US National Archives. The Russian exchange copy of the Treaty of Cession, 30 March 1867, General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; US National Archives. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph by Katie Orlinsky of melting permafrost; life in Newtok, 2019. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph reprinted with permission from Bruce F. Molnia, Ph.D., P.G.

Senior Science Advisor for National Civil Applications, US Geological Survey. Public Domain.

Senior Science Advisor for National Civil Applications, US Geological Survey. Public Domain.

Photograph reprinted with permission from Bruce F. Molnia, Ph.D., P.G.

Senior Science Advisor for National Civil Applications, US Geological Survey. Public Domain.

Senior Science Advisor for National Civil Applications, US Geological Survey. Public Domain.

Photograph by Alex Harris of Chilugan, Alaska, also known as “Chilugan,” a summer fish camp, 1977. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph by Alex Harris of marshlands, 1977. Reproduced with permission.

Relocation from Newtok to the new village site. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), House pad construction, Mertarvik/Alaska, USA, 2019. Photographs courtesy of US Senate, Office of Lisa Murkowski, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

According to the original caption: “The house pads are constructed through tundra to bedrock in order to provide a freeze-thaw stable platform. This will help build upon the progress already being made to assist the community in their village relocation efforts.” Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), House pad construction, Mertarvik/Alaska, USA, 2019. Photograph courtesy of US Senate, Office of Lisa Murkowski, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The original caption to this photograph reads: “Lance Cpl. Thomas Wendt, a heavy equipment engineer with 6th Engineer Support Battalion, Battle Creek, Mich., uses a bulldozer to spread a pile of gravel to form a base for the road. Marines with 6th ESB are building a road for the village of Newtok, Alaska. The Alaskan natives in Newtok are watching their village slowly sink into the Bering Sea.” Newtok, Alaska, 28 June 2010. Photograph by Michael Laycock, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph by Katie Orlinsky of large ponds forming in Newtok, 2019. Beyond mud, this is just open water. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph by Katie Orlinsky of Newtok boardwalks in melting tundra, 2019. Reproduced with permission.

Photograph by Alex Harris of Andrew Tommy in conversation at the fish camp, 1977. Reproduced with permission.

This photograph by Alex Harris is a portrait of reuse; hunting, airplane remnants, and permafrost melt, 1977. Reproduced with permission.

Additional Reference

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

William Least Heat-Moon, PrairyErth: A Deep Map. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999.

Mary Siisip Geniusz, Plants Have so Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask: Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

US Federal Reconstruction Grants to Municipalities, AS 37.05.315, 2011.

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press, 2014.

William Least Heat-Moon, PrairyErth: A Deep Map. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1999.

Mary Siisip Geniusz, Plants Have so Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask: Anishinaabe Botanical Teachings. Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 2015.

US Federal Reconstruction Grants to Municipalities, AS 37.05.315, 2011.

LANGTANG RIVER

Map of Langtang Park;

courtesy of author.

courtesy of author.

Babu Tamang in Langtang Park; photograph by author.

Steps are carved in and out of slopes; photograph by author.

Landslides deposit small rubble and large boulders; photograph by author.

Ammonite and Hindu saligram, Blandfordiceras wallichi, Jomosom, Nepal, Saligram Formation Late Jurassic (Tithonian), specimen #P6478. Courtesy of the University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History.

The sketch showing a typical geologic section of a slope is reproduced from A. Steck et al., “Geological Transect Across the Northwestern Himalaya in Eastern Ladakh and Lahaul (A Model for the Continental Collision of India and Asia),” Ecologae Geologicae Helvetiae 86.1 (1993): 219–63. Courtesy of the authors.

A view looking up towards

the peaks of Langtang Himal; photograph by author.

the peaks of Langtang Himal; photograph by author.

Rebuilding relies on external inputs, grading, concrete, and rebar; photograph by author.

Mani wall on the way to Mundu Village; photograph by author.

A view towards Mundu Village; photograph by author.

Digitalized herbarium sheet of Utricularia minor L. from The Herbarium Catalogue, Wisconsin State Herbarium (WIS). Record ID: e23e461a-ea3b-403d-9c98-0a88cee202e2. Image is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Looking through larch tree

silhouettes at distant slopes; photograph

by author.

silhouettes at distant slopes; photograph

by author.

The thick band in the center of this image is where Langtang Village once stood. This is the new land created by the fall of the hanging glacier. Image is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The valley in the centre of the image is filled with till and rocky debrid from the landfall, the rush of which flattered forests along the slope; photograph by author.

The Tamang owners of Lama Hotel; photograph by author.

A typical scene along our walk,

quick landslides and lazy dzo; photograph by author.

quick landslides and lazy dzo; photograph by author.

All along the rockfall that buried Langtang Village, residents were trying to encourage life, creating mounds of soil and growing plants; photograph by author.

Winter dormancy made identifying fruiting and flowering plants a challenge; photograph by author.

The interior of a traditional home where we drank warm yak milk hearted by dung patties; photograph by author.

We visited traditional homes in Mundu village, since all the homes were destroyed in Langtang; photograph by author.

We were told that the translation for amchi was “healer” or medicine man. Here he is, posing outside his home in Mundu village; photograph by author.

Photograph of border to Langtang Park, Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation; photograph by author.

The last house standing at the edge of the landslide that buried Langtang Village; photograph by author.

The joy of finding new plants, especially those thriving in winter; photograph by author.

A stand of poplar trees, a clonal plant that thrives with disturbance; photograph by author.

Crossing the Langtang rockfall is tough going for all of us, including the donkeys; photograph by author.

Additional References

Rebecca Solnit, “Footwork.” Grand Street 63 (1998): 146–52.

Thomas King, The Truth About Stories. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2003.

Rebecca Solnit, “Footwork.” Grand Street 63 (1998): 146–52.

Thomas King, The Truth About Stories. Toronto: House of Anansi Press, 2003.

GASPÉSIE PENINSULA

Map of Sainte-Flavie; courtesy

of author.

of author.

View across Saint Lawrence River towards the shores of Sainte-Flavie; photograph by Mariel Collard Arias.

Diving in the Saint Lawrence River. Photograph by Isabelle-Côté. Courtesy of Dr. Ladd Johnson, Johnson Benthic Ecology Laboratory, Département de biologie, Université Laval.

The tidal shores of the river teem with seaweed; photograph by author.

Ice flows along the Saint Lawrence River; photograph by author.

This map entitled “Carte de la rivière de Québec” dates from between 1715 and 1777, likely before the River was named Sainte Lawrence. Reproduced from Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE SH 18 PF 126 DIV 1 P 2, Manuscript and cartographic resource, 1 carte : ms, col. ; 46.5 x 101.5 cm, 1715–77. Public Domain.

The shoreline of the Sainte Lawrence is a floodplain, and poses a risk to fixed settlement. Photograph by Jean Bastien, “Big storm of December 6, 1949, that damaged eleven houses between Cap-Chat and Sainte-Anne-des-Monts, Gaspé-Nord County.” Ministère de la Culture et des Communications Fonds Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec E6 S7 SS1 P74771. Reproduced with permission.

View along the shore at Sainte Luce-sur-Mer, a popular beach; photograph by Mariel Collard Arias.

Aerial image of the shoreline near Metis, connected along the shoreline with Sainte-Flavie. Photograph courtesy of Les Amis des Jardins de Métis Collection. Reproduced with permission.

The region’s metropolis and aspirations were part of a road-based strategy of connection along the shore. Postcard, 1960s [exact date unknown]. Photograph courtesy of Les Amis des Jardins de Métis Collection. Reproduced with permission.

Map of railroad speculation by Polydor (J.P.) Dutil Série documentaire: Arpentage des terres du domaine de l’État et des frontières du Québec. Catégorie: Plan, Chemin de Fer Roulé. Date: 1928-09-11 Document: 9-S, Chemin de fer Intercolonial. Public Domain.

Erosion along Route 132. Photographs private collection. Reproduced with permission.

Resident Pierre Bouchard shows reporters the remains of his home after the high tides in 2010. Photograph by Catherine Legault for Le Devoir, 2010. Reproduced with permission.

The landscape of retreat is pronounced when houses are demolished and an empty lot is left behind; photograph by author.

This map shows the constraints to development due to erosion, which significantly overlaps most of the small town of Sainte-Flavie. Image courtesy of the Government of Quebec. Reprinted from: “Zones de constraints relatives à l’érosion côtière,” Gouvernement du Québec, Dépôt Légal-Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, 2e trimestre, 2017. Reproduced with permission.

All drone photographs in this section are by Mariel Collard Arias. Reproduced with permission.

View along the shore: Mariel Collard Arias, Guadalupe Fernandez, and Rosetta S. Elkin are testing the drone; photograph by Mariel Collard Arias.

Coming to terms with the scale of snow; photograph by author.

Mariel Collard Arias operating her drone; photograph by author.

A house typical of traditional shoreline construction, currently held to the ground by aeroplane cables; photograph by author.

Additional References

Herman Melville, Moby Dick; or, The Whale. New York: Penguin, 1992.

Alexander Reford, “Touring the Gapse Peninsula: The Hisotry of an Epic Road Trip,” in Community Stories, Digital Museums of Canada (2019). communitystories.ca.

Laurent Salinas, resident of Sainte-Flavie, from “Il y a dix ans, les grandes marées frappaient l’Est-du-Québec de plein fouet.” ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1754883/grandes-marees-decembre-2010-tempete-saint-flavie-luce-vagues.

Margaret Atwood, “February” in Morning in the Burned House (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995).

Herman Melville, Moby Dick; or, The Whale. New York: Penguin, 1992.

Alexander Reford, “Touring the Gapse Peninsula: The Hisotry of an Epic Road Trip,” in Community Stories, Digital Museums of Canada (2019). communitystories.ca.

Laurent Salinas, resident of Sainte-Flavie, from “Il y a dix ans, les grandes marées frappaient l’Est-du-Québec de plein fouet.” ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1754883/grandes-marees-decembre-2010-tempete-saint-flavie-luce-vagues.

Margaret Atwood, “February” in Morning in the Burned House (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1995).