MAULE RIVER

Talca Province, Chile

The Chilean coast suffered a tsunami triggered by an earthquake in 2010, creating after-effects that continue to flow upstream. Each upstream effect suggests that a single “natural” event is not where the damage lies, rather it is found in the layers of long-term, systemic damage initiated by unnatural causes. The tsunami laid bare the past. Making sense of the resulting friction is a challenge for researchers because the Chilean coast, as a largely industrialized zone, is the

result of centuries-long and ongoing exploitation. The procedures that scar the present include plantation forestry and the forced removal of Indigenous cultures. How can events be studied in the present without obscuring the past? Perhaps by tracing a description of a recent

event that exposes the overlap in otherwise disparate histories, between displacement and settlement, and among rivers, plantations, soils, and stories. A kind of narrative repair that commits to understanding more than accusation. My ambition in this case study is to learn how to better approach a vulnerable, injured landscape through creative research that pays attention to multigenerational and multispecies stories that survive despite the odds. After all, it is not only humans that make history. Diversifying our stories helps shed light both on how we inherit the past and how we might share the future.

The Estuary from

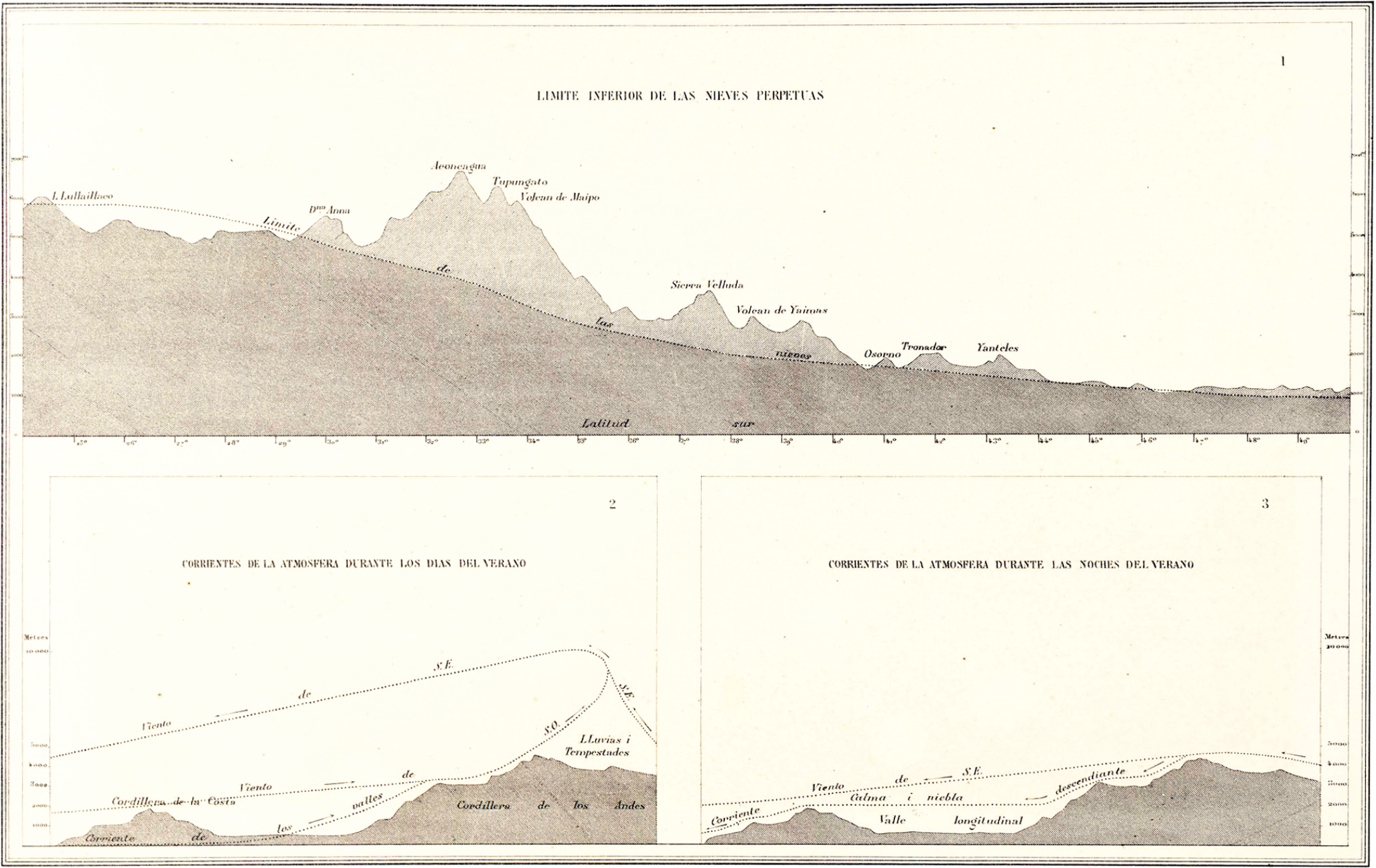

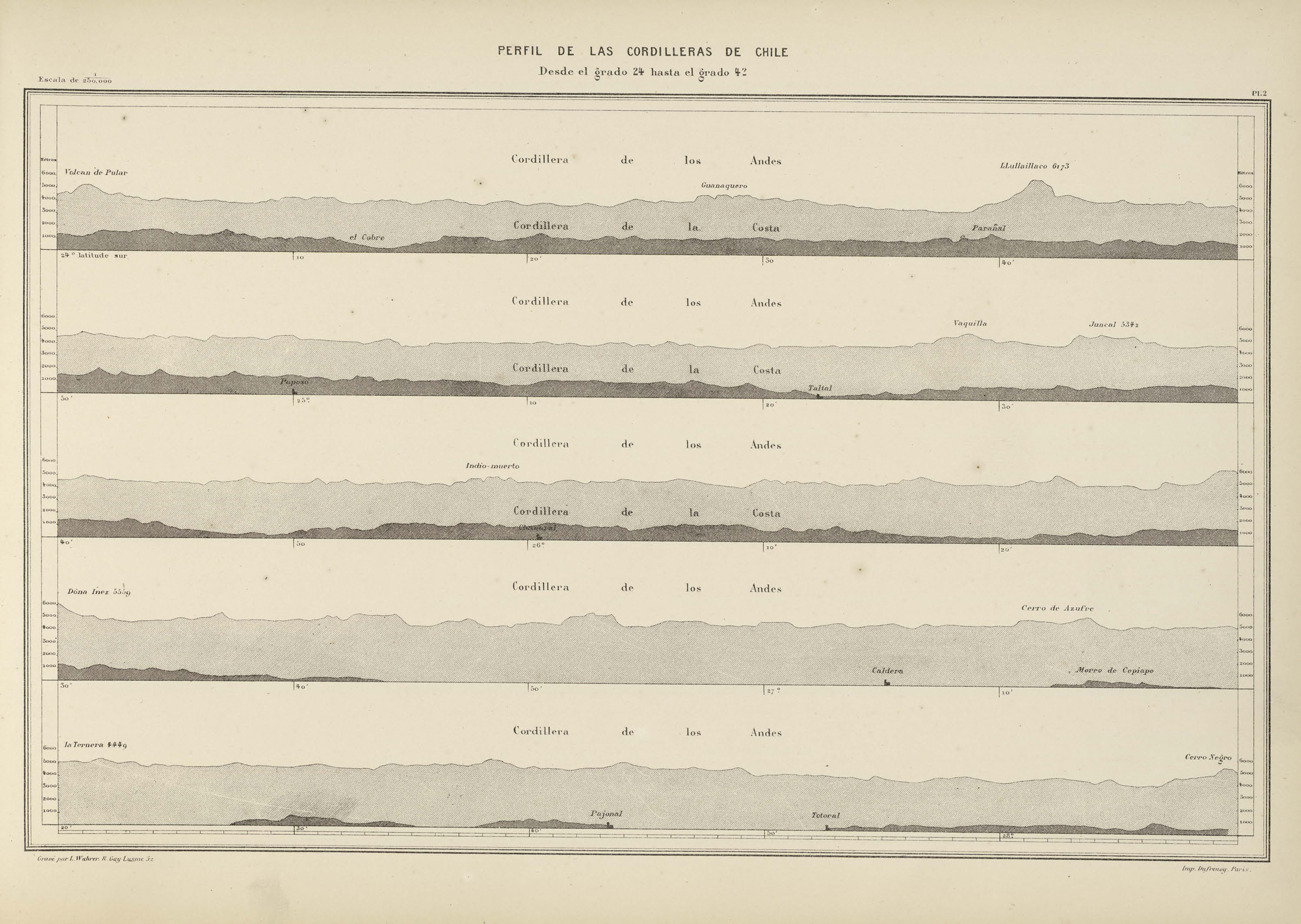

There are so many rivers along south-central Chile that the coastline is not so much a terrestrial edge, but a series of estuaries. Chile is typically understood from the mountains to the sea, a transect that rises in the Andes, flows along multiple rivers, intersects with low valleys, as water slows and irrigates cultivation before it reaches saltwater, and eventually the Pacific. The varied elevation along each estuarine setting distinguishes the rate of freshwater flow and the amount of seawater from the ocean, as life mingles, gathers, and circulates across tectonic boundaries. Those who seek boundaries will only find silty deposits, layered somewhere between above and below tides. Each layer is animated by wave action and reconfigured during tsunami events.

On 27 February 2010, an earthquake activated a tsunami deep below the Pacific Ocean, violently transporting marine waters towards estuarine geology, displacing the silty layers of each terrestrial elevation regardless of human possession, ritual, or safety. The official classification recorded 8.8 in magnitude, while the intensity of the earthquake was measured as IX class. The earthquake force triggered a devastating tsunami towards the coast of Chile, while it also generated unusually strong waves as far away as Indonesia, over 17,000 kilometers across the Pacific Ocean.

“Growing up, we learn Chile’s geography through a cut from east to west so that you see Argentina, big mountains, small mountains, ocean. But it is interesting that nobody cut Chile from Patagonia to Peru to show us all these little valleys between rivers, near estuaries. This is what gives us identity. There are similarities between people living in the mountains, the central valleys, or the coast, but when you go from valley to valley, from north to south, every river is different and defines people’s personalities, lifestyles, sense of humor. I think we should talk about our culture from valley to valley.”

result of centuries-long and ongoing exploitation. The procedures that scar the present include plantation forestry and the forced removal of Indigenous cultures. How can events be studied in the present without obscuring the past? Perhaps by tracing a description of a recent

event that exposes the overlap in otherwise disparate histories, between displacement and settlement, and among rivers, plantations, soils, and stories. A kind of narrative repair that commits to understanding more than accusation. My ambition in this case study is to learn how to better approach a vulnerable, injured landscape through creative research that pays attention to multigenerational and multispecies stories that survive despite the odds. After all, it is not only humans that make history. Diversifying our stories helps shed light both on how we inherit the past and how we might share the future.

The Estuary from

Earthquake to Tsunami

There are so many rivers along south-central Chile that the coastline is not so much a terrestrial edge, but a series of estuaries. Chile is typically understood from the mountains to the sea, a transect that rises in the Andes, flows along multiple rivers, intersects with low valleys, as water slows and irrigates cultivation before it reaches saltwater, and eventually the Pacific. The varied elevation along each estuarine setting distinguishes the rate of freshwater flow and the amount of seawater from the ocean, as life mingles, gathers, and circulates across tectonic boundaries. Those who seek boundaries will only find silty deposits, layered somewhere between above and below tides. Each layer is animated by wave action and reconfigured during tsunami events.

On 27 February 2010, an earthquake activated a tsunami deep below the Pacific Ocean, violently transporting marine waters towards estuarine geology, displacing the silty layers of each terrestrial elevation regardless of human possession, ritual, or safety. The official classification recorded 8.8 in magnitude, while the intensity of the earthquake was measured as IX class. The earthquake force triggered a devastating tsunami towards the coast of Chile, while it also generated unusually strong waves as far away as Indonesia, over 17,000 kilometers across the Pacific Ocean.

“Growing up, we learn Chile’s geography through a cut from east to west so that you see Argentina, big mountains, small mountains, ocean. But it is interesting that nobody cut Chile from Patagonia to Peru to show us all these little valleys between rivers, near estuaries. This is what gives us identity. There are similarities between people living in the mountains, the central valleys, or the coast, but when you go from valley to valley, from north to south, every river is different and defines people’s personalities, lifestyles, sense of humor. I think we should talk about our culture from valley to valley.”

1

Interview with Pablo Gonzalez, 16 October 2018.

— Pablo González, kayak trip leader

The Maule River estuary outfalls at Constitución, one of the hardest hit communities following the tsunami in 2010. Extreme pulses of inundation are common to estuarine environments where marine sand meets river silt. At present, many estuaries along the Chilean coast are infilled by coastal concretization that intervenes between marine and terrestrial realms.

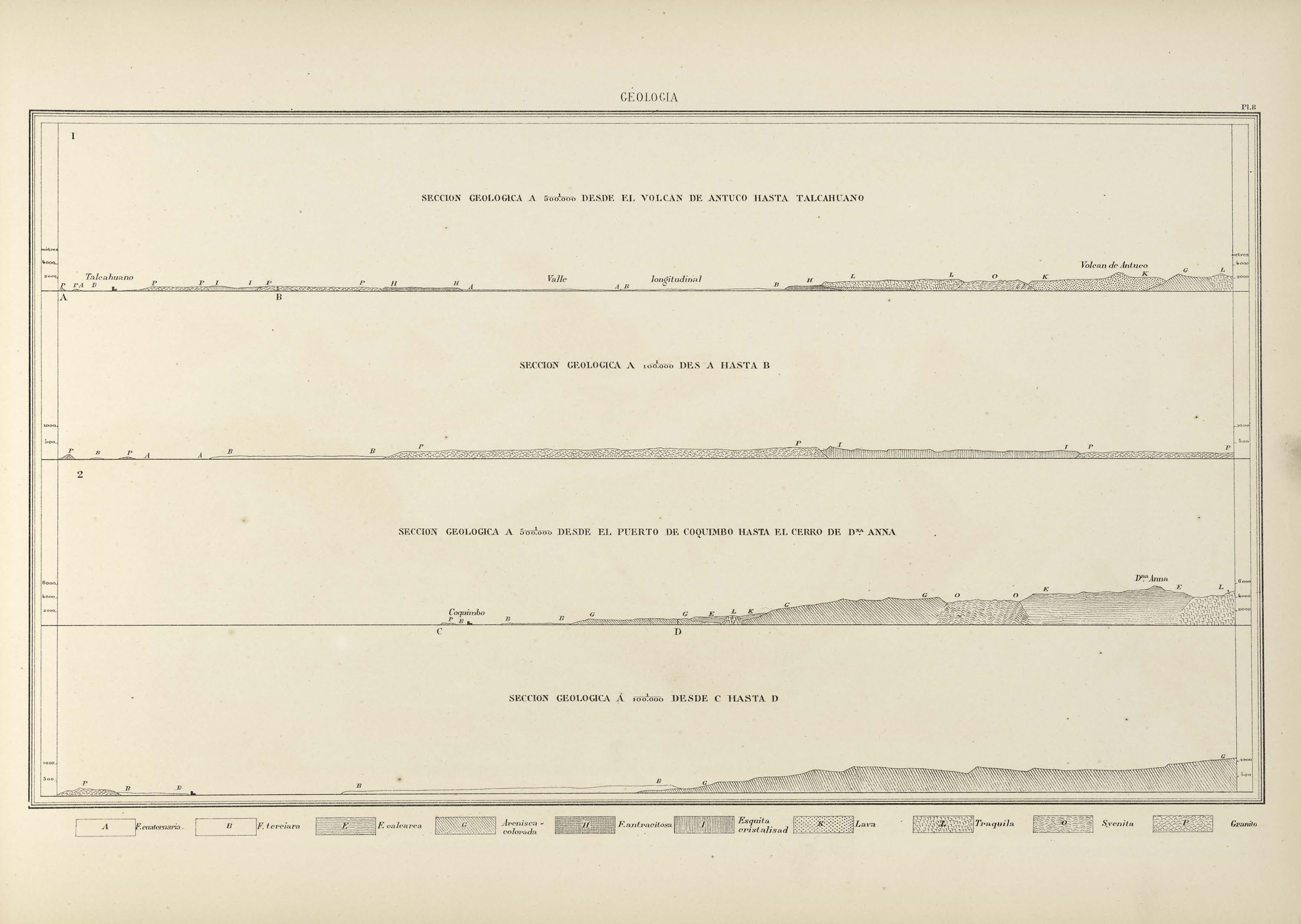

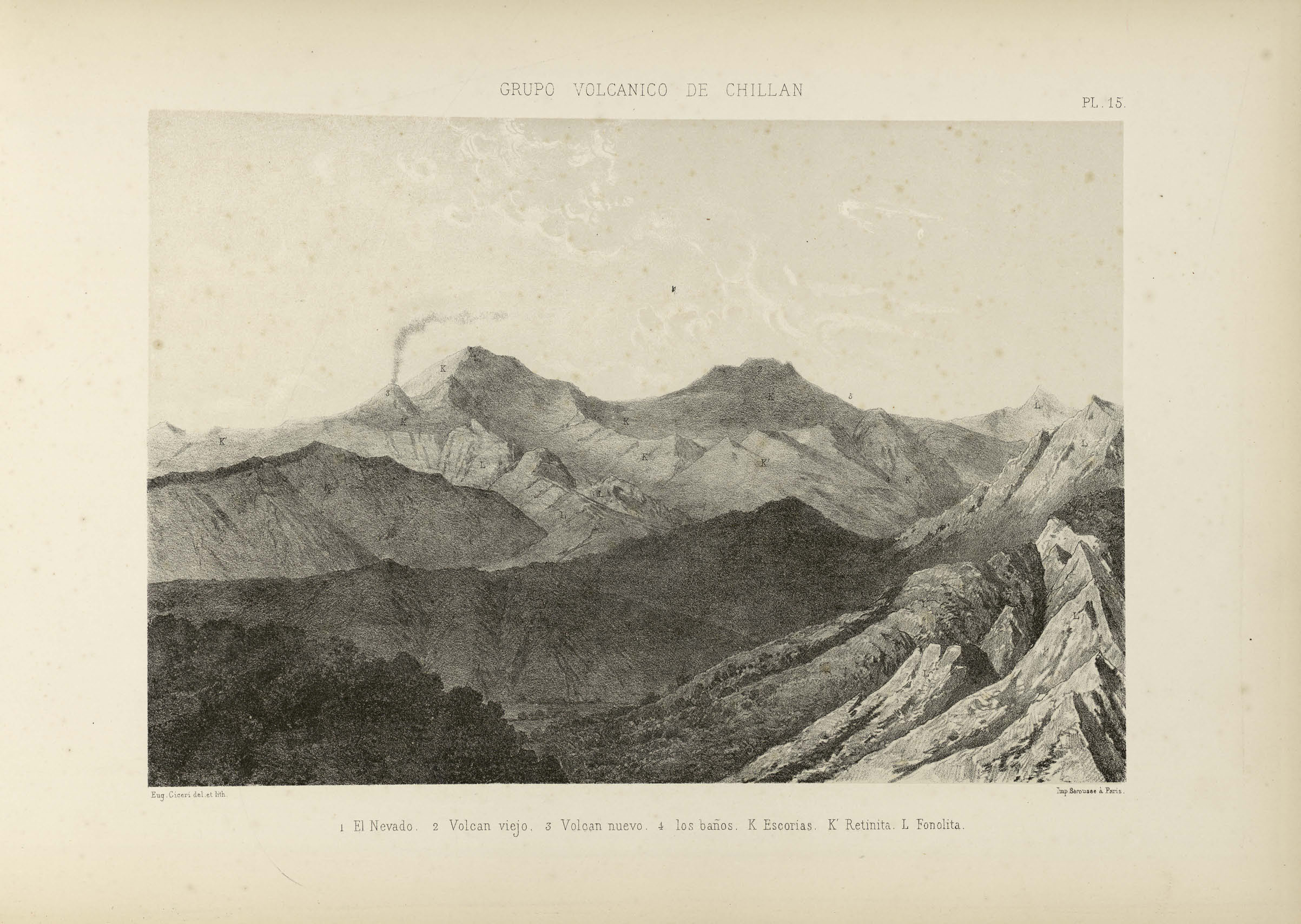

The wave action following an earthquake brought silty inundation, erosion, and deposition to the estuarine coast, a disturbance that is neither unprecedented nor particularly unique. The lineage of estuary formation across time is described by paleo-geological

analysis which confirms that the southwest coast of

Chile is a remarkably active area on t

A rupture twenty-five kilometers deep beneath the Nazca plate, produced the earthquake, triggering a tsunami that traveled along the

fault at tectonic junctions. The magnitudinous waves spread beneath the coast until making landfall along the shores between Constitución and Concepción. Magnitude is relative power, and its measurement takes into account the energy released at the source. By comparison, intensity is the strength of the shaking produced by the magnitude.

The Maule River estuary outfalls at Constitución, one

of the hardest hit communities following the tsunami

in 2010. Extreme pulses of inundation are common

to these environments where marine sand meets

river silt. At present, many estuaries along the Chilean

coast are infilled by coastal concretization that intervenes

between marine and terrestrial realms. The

wave action following an earthquake brought silty

inundation, erosion, and deposition to the estuarine

coast, a disturbance that is neither unprecedented

nor particularly unique. The lineage of estuary formation

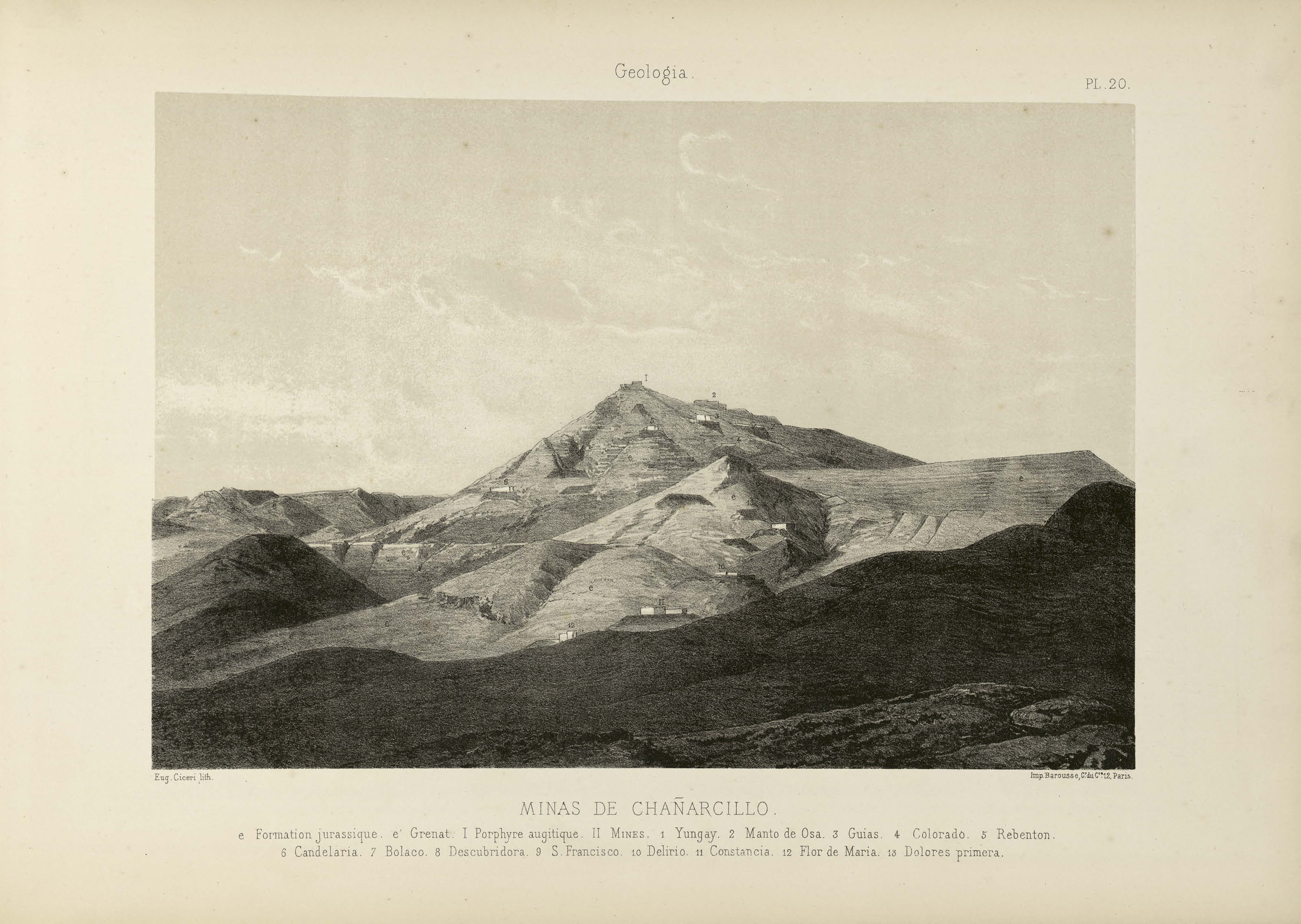

across time is described by early mapping efforts

that creatively articulate the watery southwest

coast of Chile.

A rupture twenty-five kilometers deep beneath the Nazca plate, produced the earthquake, triggering a tsunami that traveled along the

fault at tectonic junctions. The magnitudinous waves spread beneath the coast until making landfall along the shores between Constitución and Concepción. Magnitude is relative power, and its measurement takes into account the energy released at the source. By comparison, intensity is the strength of the shaking produced by the magnitude.

During a tsunami, the existing boundaries of any estuary are forced to shift or migrate, often significantly changing the channel dynamics upstream. As the energy transfers upstream, it forces waters inland, causing silty sediments to find temporary repose across riverbanks, floodplains, and shorelines. The different stages between the trembling of the ground, and a tidal wave rising is a period where fractures and fissures develop, a time of fearful memory according to Charles Darwin, who experienced the 1835 earthquake along the Chilean coast. Darwin recounted the effect with the kind of logical detachment associated with his voyages: “First, at the instant of the shock, the water swells high up on the beach with a gentle motion, and then as quietly retreats; secondly, sometime afterwards, the whole body of the sea retires from the coast, and then returns in waves of overwhelming force. The first movement seems to be an immediate consequence of the earthquake affecting differently a fluid and a solid, so that their respective levels are slightly deranged: but the second case is a far more important phenomenon.”

Although the word estuary is a noun, it can be translated to aestuarium in Latin, which comes from aestus—an opening. The associa- tion with estuary as an action or occurrence indicates that “estuary” might be reconfigured as a verb. If so, then the 2010 tsunami estuaried the coastline, mudflats, islands, and the town of Constitución.

The dynamic formation that estuaries a setting is analyzed by geologists in layers, lateral deposits that read like tree-rings set deep into the shoreline. But tsunamis do not form rings, they deposit lateral marine sands in thick bands. Each layer chronicles tsunami events. The thickness of marine sand sheets also validates historic record, unwritten or otherwise oral accounts by providing material evidence of each event. The “event beds” near Constitución can be read as far back as 1575 and include major events in 1835 and 1960. Such deep analysis is the territory of paleo-studies, associating the present with a past that confirms estuarine behavior. In the present, the issue is contoured by policy, by risk-assessment that arises from earthquake prone areas. The tsunami actions that estuary the coast are not presnt in the measures associated with current risk. This translates to a community prepared for earthquakes, but negligent of tsunamis. The endless formation of the southwest coast of Chile is a region activated by tectonics and scientists, an experience that congregates around geologic diversity in charts, tables, and monitoring. The dynamic formations that estuary the coast are hidden from the human community, obscured by a century of industrial activity.

On 20 February 1835, Charles Darwin was in the forest above Concepción, and he describes the after-effects of the earthquake and tsunami once he reached the shores and spoke with his fellow travelers. Of particular interest is the difference between these two experiences:

2

Charles Darwin, Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle round the world (London: John Murray, 1876), 519.

The return of the whole body of the sea depicts the approach as ocean waters encounter coastal geology, rushing upstream with irresistible force, often physically transforming the shoreline by raising the elevation with its silty deposits. Wherever coastal or riverine geology is made up of hardened infrastructure, the force meets seawalls, foundations, and embankments that destroy estuarine subtleties and replace the possibility of physical reconfiguration with the reality of destruction.Although the word estuary is a noun, it can be translated to aestuarium in Latin, which comes from aestus—an opening. The associa- tion with estuary as an action or occurrence indicates that “estuary” might be reconfigured as a verb. If so, then the 2010 tsunami estuaried the coastline, mudflats, islands, and the town of Constitución.

The dynamic formation that estuaries a setting is analyzed by geologists in layers, lateral deposits that read like tree-rings set deep into the shoreline. But tsunamis do not form rings, they deposit lateral marine sands in thick bands. Each layer chronicles tsunami events. The thickness of marine sand sheets also validates historic record, unwritten or otherwise oral accounts by providing material evidence of each event. The “event beds” near Constitución can be read as far back as 1575 and include major events in 1835 and 1960. Such deep analysis is the territory of paleo-studies, associating the present with a past that confirms estuarine behavior. In the present, the issue is contoured by policy, by risk-assessment that arises from earthquake prone areas. The tsunami actions that estuary the coast are not presnt in the measures associated with current risk. This translates to a community prepared for earthquakes, but negligent of tsunamis. The endless formation of the southwest coast of Chile is a region activated by tectonics and scientists, an experience that congregates around geologic diversity in charts, tables, and monitoring. The dynamic formations that estuary the coast are hidden from the human community, obscured by a century of industrial activity.

On 20 February 1835, Charles Darwin was in the forest above Concepción, and he describes the after-effects of the earthquake and tsunami once he reached the shores and spoke with his fellow travelers. Of particular interest is the difference between these two experiences:

“A bad earthquake at once destroys our oldest associations: the earth, the very emblem of solidity, has moved beneath our feet like a thin crust over a fluid; one second of time has created in the mind a strange idea of insecurity, which hours of reflection would not have produced. In the forest, as a breeze moved the trees, I felt only the earth tremble, but saw no other effect. Captain Fitzroy and some officers were at the town during the shock, and there the scene was more striking; for although the houses, from being built of wood, did not fall, they were violently shaken, and the boards creaked and rattled together. The people rushed out of doors in the greatest alarm. It is these accompaniments that create that perfect horror of earthquakes, experienced by all who have thus seen, as well as felt, their effects. Within the forest it was a deeply interesting, but by no means an awe-exciting phenomenon.”

3

Charles Darwin, Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle round the world (London: John Murray, 1876), 522.

— Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle

WHAT KIND OF WISDOM CAN WE SHARE?

A Conversation with Bernardo Reyes

We met with Bernardo Reyes because he is an activist and ecologist. But we learned from Bernardo because he approaches his work as a collaboration. His efforts are land-based, he works to stop the spread of plantations, to support the liv- ing traditions of Mapuche nations, and to defend waters from pesticides and dams. Each confrontation is not ecological, it is found in the conflict between the forestry industry and Mapuche land claims.

14 October 2018, Santiago, Chile

14 October 2018, Santiago, Chile

BERNARDO REYES

Do you know that the male frog keeps the eggs in is mouth until they hatch? For fourteen days the frog gets skinnier and skinnier because he is taking care of the babies. Isn’t it unusual that a male will go out of their way for the protection of others? We call this frog the blue frog (Rhinoderma darwinii). I don’t know why because it is green or brown and has black and white spots on his belly.So what about the blue fox? This is the fox (Lycalopex fulvipes) that used to walk with the Mapuche wizard before the Spaniards took hold. The wizard would not go into Nahuelbuta Mountain without the permission and the company of the blue fox, the instructor and secrets keeper. This approachable, friendly fox is the true source of Chilean knowledge.

ROSETTA S. ELKIN

Can you tell us about how you work with the Mapuche within a long and fragmented history of conflict between forests and plantations?B R

It is important to know that plantations are not forests. A plantation is a procedure that funds tree planting so that they can be cut down. In Chile, when you mention planted forests

you create a confrontation with language. About twelve years ago, Grupo Matte—the second largest company in Chile, owned by one the richest and most influential families—started a campaign called “Estamos plantando bosques para Chile.” This translates to: “We are planting forests for Chile,” in Spanish, bosques means forests. Which is where the confrontation begins, because tree plantations are industrial crops. Nothing wrong with an industrial crop, but they are not forests. A forest is a circular system of relationships, absolutely integrated because nothing is ever wasted. But how can you draw relationships?We have to think of the forests as the cradle of water. Without forests we have no low-pressure systems. Without low-pressure systems there can be no clouds. Coastal forests are especialy good at carrying in low-pressure systems, bringing clouds and moist re from the ocean all the way into the continent. So, if we are going to be serious about climate change, we should be helping build or rebuilding and provide the conditions for the forest to come back again. The most relevant components of ecosystems are not visible to human beings.

R S E

This is why forestry professionals outline the tree, give it a form and an outline. This allows corporations to hide behind an image, the tree as an object that can be defined, priced, measured, traded. Trees—or plantations—are standing capital; once objectified, they represent economic value. On the other hand, root systems, chemical coordination, or the inter-relationships with humansand other creatures cannot be easily objectified, so they are cast aside both physically and intellectually.B R

We are monocropping the planet, and we can certainly not monocrop the planet without monocropping our system of knowledge. This only represents “techno-knowledge,” a technical fix. What about the knowledge found in bacteria, the lichens, the viruses, they are all in a dialogue, building with and dealing with very complex problems. Those relationships provide the conditions for the forest to come back. This is an intellectual capacity—not a human one—one of intelligent cooperation. That is why definitions and boundaries are important, because they are being fabricated by forestry standards, rather than shaped by respect.R S E

How do you work through the generic definitions of words such as territory, forest, or even landscape? What are the differences? And how do these differences in language translate between indigenous meanings, academic definitions, industrial, or even marketing explanations? The role of language resonates in your earlier statement that “plantations are not forests.”B R

This is an emerging dialogue,for instance for a Mapuche, trayencho is translated as “spring,” where water comes out of the earth. But for a Mapuche a trayencho is also much more than a spring. In Spanish, the translation is ojo de agua or manantial, in Mapuche language, trayencho is all the area of land and plants that live and create the conditions for the water to flow. So what are the boundaries?

Why be interested in boundaries? I defend language because we have suffered a tsunami of Pine and Eucalyptus plantations, and that tsunami has destroyed the central coastal mountain range. This creates a tension with the people that live there who are being told, generation after generation, that this is a forest. I tell them no. This is not a forest, they are being sucked into using the same language as the forestry companies. Even engineers talk about forests when they mean plantations.

The Mapuche have their own set of beliefs and categories of knowledge that are not particularly physical. They are intangible. Mapuche believe that ko, water, is the spirit. Ko cannot remain healthy nor provide health if it doesn’t have ngen—the spirit of ko. So “ngen ko” is the spirit of water. And the spirit of water is only viable if the plants

are thriving because they provide the conditions healthy water. That is a love relationship. What we want to be able to say is that plants belong to the trayencho. For instance, that might mean pines should not be planted closer than fifteen meters away from. But the law says it is legal to plant as close as five meters near the spring. This is too close because the plantation will suck up the water. So, we are engaging in a dialogue with the Mapuche people to raise the level of respect for the trayencho, to remove the pines within a broader area. The word we use is cohabitation because Mapuche health depends on their plants and the ko only lives if there are plants around. We don’t want to stop the plantations; we want to push them back. Recently, some of the largest tree plantations were approved in that area, so it is where you find the strongest confrontations between the forestry system and the Mapuche land claims. It is a difficult area to work in but there is hope. For instance, we managed to stop conversion of native forest into plantations with a large campaign from 2001 to 2003 that led to a formal, public agreement. So we move on to the next issue, which involves pressuring the industry to conserve and study the zones of native or remnant forests, to increase knowledge and create sanctuaries.

The Mapuche also have different categories of knowledge in their systems that are not linguistic. They talk about their intangible patrimony within the forest. The forest is part ritual, part heritage. And the plantation is nothing. The plantation replaces the forest and denatures the intangible aspects of a culture. For example, if plantations are spread across our mountain ranges, then suddenly there is no longer an echo. The echo is gone. Does the industry think about the role of an echo in society? No. But in Maphuche culture, echos can communicate. In Mapolingun, an echo is ow Kinko.

Bernardo goes on to explain that Mapuche call up the hills to communicate, not through the trees, but with the forest. He gives an example: “Daaaad! Lunch, Dad! Luuunch,” as he cups his hand around his mouth to express the cry for a meal, a sound directed uphill. Bernardo describes how the father will hear that it is lunch through the echo and come down from the hills. He explains how sound travels in a forest, bouncing and darting, absorbing and attracting tone: “The echo is an intangible but reliable infrastructure of communication.” But in a monoculture plantation, he explains, there is no more sound. A loss of communication that has evolved over thousands of years, between humans and with the forest as an active medium. Because of plantations, the ow Kinko is gone.

B R

One part of our work is called “the forest dialogue system.” The most diffi- cult part of that work is not about find- ing the means to work with Mapuche, who value the forest, the challenge is how to work with the Chileans who live in the area. A segment of the commu- nity grew up with the expectation that they will make money from the tree plantations. And they do not miss the forest because they have never seen it. At the same time, most are unemployed and frustrated because there is no longer any money to be made in the planta- tions, yet they watch the forestry com- panies prosper. Because they were raised to see the land as standing value, many Chileans easily fragment, create parcels, timber. So they are always looking to make money off the land rather than learn from the land. These are different cultures, residing together and the question is how we value relationships between groups with different expectations and different social principles. The task is both complex and beautiful.R S E

We are trying to pay attentio to the concealed relationships that create landscape. To find out what the intangible infrastructure of retreat looks like, despite the global policy to either rebuild or restore. When a landscape and its inhabitants suffer a eucalyptus and pine tsunami, a hanging glacier that shifts with warming, or the effects of not-so permafrost, relationships to the land are replaced by insurance claims, real estate markets, compliance standards, and legal operators. What is it about your work, life, and activism that inspires you to continue to collaborate with intangibles, on a planet obsessed with material gain?B R

First, we have to believe it is possible to push against the forestry model. What I am interested in is the good news, because there is a feeling that everything is wrong, corrupt, and people are beginning to sink from all the bad news. This means that people begin to build fences, to fence their minds. If we don’t make change we are giving up. It is everywhere and it is personal. The minute you decide that you will reduce from 3,000 gadgets to 1,000 gadgets in your home you are making a change. When you simplify your life, you begin to push back on the model.I am an ecologist by trade, but I survived teaching at an architecture school because it was an alternative school and they let me teach most of my classes outside. Here, the students could learn their territory, learn how our roads break the link between people, communities, other species, and the mountains. Interestingly, the Andes really do not have a strong impact on our culture, yet we are really pretty close to them. This is a narrow country, yet we are also not a maritime people. Instead, we consider ourselves a fishing country, because our main export is fish. This is our wealth. Now we are wealthy people who do not know their territory. For instance, not one, but three presidents and several ministers say that the rivers are wasting water by emptying into the sea, which of course means that they need to be dammed to “save” the water. But how does the sea get wealthy?

I took a group of students out to the mountains recently. I said: “Let’s lie down in a circle.” They said: “It’s a bit humid, no?” I was surprised because no one wanted to lie on the ground in this incredible place, so I said: “C’mon guys, there are leaves, make a circle. But no one wanted to be on the ground because it was dirty. I just wanted them to be quiet, to become a microphone for the insects and the wind. I told them that they could not be architects without understanding nature.

There is no way I can apply any more of my energy to the university system, I do not have that much energy. So, I must decide where to put my time, and I want to put it where I can grow knowledge. And knowledge is not shared in institutions anymore. At the end it is not the institution or the NGO but the learning structure. How you process local knowledge, not for knowledge’s sake but for wisdom. If the issue was wisdom we would have no universities or NGOs, we do not need them to process and administer wisdom.

We met with Bernardo for just these kinds of insights. It begins with a story, as we gain mutual respect and understanding for one another. The struggle to defend the landscape, include Indigenous knowledge and appreciate the alterations brought about by climate change are unified topics that are often divided. They were divided across Bernardo’s career, as they are divided in mine. The startling truth is that these topics remain siloed in his time as well. At this point, Bernardo sits back and sighs: “Why do we complicate life?”

R S E

The view that Native peoples are incapable of managing their own lands in intelligent ways is at the center of settler colonialism. Plantations derive from centuries of violence, and the systematized effort to remove individuals from the land. B R

After the war with Bolivia and Perú, the Chilean army was ready to increase or expand the internal frontiers that meant to “pacify” the Indians and put them into reservations. That war lasted from 1881 to 1883, and the army moved in to forcefully put people into reservations, take away their land, and introduce massive programs to bring in European settlers to make land produce because, for them, the Indians werenot creating wealth. The Mapuche got shifted around a lot. That extended for about twenty years. It is very similar to the founding of the United States and Canada.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the official story was that nations, including the Mapuche were fighting all the time, attacking the cities so they had to be kept away because it wasn’t safe. They were the people who lost their entitlement to land, and in through their landlessness they were a burden to the state. The idea of an agrarian reform was an opportunity to bring about certain degree of equality in the countryside for the landless. During Allende’s government I was very young, but we were very involved in politics then.

R S E

In Chile, the forestry plantations are further corrupted by advances in biotechnology. The plantations are composed of only two plant species: Pine and Eucalyptus. And each species is a clone, so Chilean plantations only have a single DNA. Do people notice that diversity was destroyed during the transformation?B R

No. Most people don’t see it that way. We work with stories, multigenerational knowledge, and preservation pilots to explain it. Women collecting and restoring, men working on tourism, small conservation groups, schools, local water organizations, those are the networks we are building to push back the plantations.Mapuche and the people that work the land see it and describe how “there used to be a small stream here, or a spring emerged there. They indicate how in a eucalyptus plantation, water is gone because these plants are so greedy about the water. Foresters often ask ecologists questions like: “Once the eucalyptus is felled, how long will it take before we can replant?” They are asking because they have learned since the 1980s that as the industry gains profit, the wood from the trees basically retains the same value. They grow timber, but the industry can only turn it into a resource if there is demand.

When demand falls, plantations appear inadequate. So now foresters ask ecologists: “How can we turn a plantation back into a more diverse set of agricultural products?” I tell them it is not so simple. We cannot keep treating the land as a machine for making resources. So we are showing them that it is not about production, it is about regeneration. Without the assistance of bacteria in the soils, the plants will not grow. Our team brings microscopes and we show them the little nodules and say, “Hey, guys! We can show you the multitude of species that it takes to start regenerating land.”

Although there is a lot of talk about restoration, what we need to be considering is regenerating our lost practices, because we no longer understand how the earth revives. We need to learn it again and it cannot be found in books. This is not production, it is action—so we do not write books, we develop practices.

R S E

I couldn’t agree more! The labor of maintenance, foraging, cultivation, and gardening are at the core of land-based practices. Can you share an example with us?1. Often called cultura de campamento, this translates roughly to camp-band culture in reference to those who follow forestry and mining for work in someone else’s territory, and come home for a few days before they go out again to clear-cut trees and extract materials.

2. Headwaters are the smallest streams that feed into different parts of a river network. They are the part of rivers furthest from the river’s endpoint or confluence where they mingle with another water- body. In Chile, this is typically at the estuary where its many rivers meet the Pacific.

B R

We have a network of women (Contulmo) who do not work with the forestry industry; therefore they stay closer to villages, unlike the men who have to move around the country for clear-cutting.1 But the women who stay behind usually take care of the home-steads and the animals, make food and subsist from the forest, not the plantations. They are free from the forestry industry but they are dependent on what I call the crevices, the last, fine remains of the forests. They are cash poor, but they collect food and even sell plants, seeds, or mushrooms for healing. The knowledge of those crevices is maintained by their practices. Another example falls under the heading of restoration, even though the forestry companies are pouring Round-up into the headwaters.2 This means that everybody living downstream will end up drinking small amounts of glypho- sate herbicide from the Roundup.

They are using it to suppress sprouts from the eucalyptus stumps. It is easy to walk around with a mask and spray the soil. Our practice is to put a black blanket over the stump. It’s simple; just deprive the eucalyptus of sunlight. But it is very hard to work with the foresters; their first reaction to our suggestion to move away from glyphosate herbicide was to buy rolls and rolls of black plastic! Plastic of course is non-biodegradable, and there are other black materials. We ask ourselves, when somebody comes from the outside, what kind of wisdom can we share?

The sun is setting, we’ve eaten two meals, sipped lemonade in the strong sun, and tea in the late afternoon. Bernardo’s family keeps coming in and out, generations overlapping, asking us questions, and finding common ground. There is

a cat whose name I cannot remember, but she acts the part, alternatively frisky or lazy. Mariel and I are tired from the flight, and have a long drive ahead of us to reach El Maule. I mention the kayaking and camping ahead of us to Bernardo and he replies:

I’m walking rivers now, I don’t paddle that much anymore. I walk the rivers from the top of the mountains all the way to the sea or vice versa and I do it alone, because otherwise you don’t clean your brain. Rivers have a language for hundreds of centuries so if you want to understand them, the opportunity is there. A river is never the same year after year; they are shifting systems, particularly the large ones. That’s what I see myself doing hopefully for the rest of my life, hopefully full-time. [Laughter] There are so many rivers to walk and so much you can learn from them.

Bernardo Reyes is an ecologist and activist who travels on foot and on horseback. As Director of Etica en los Bosques (EEB), he is dedicated to the protection and restoration of forest ecosystems in Chile. Bernardo leads teams that provide sup- port to various local organizations such as the collectors of non-timber forest products or the cooperative of Nahuelbuta restorers, among other local organiza- tions that promote the protection of forests, biodiversity, rivers, and cultural spaces and processes.