During a tsunami, the existing boundaries of any estuary are forced to shift or migrate, often significantly changing the channel dynamics upstream. As the energy transfers upstream, it forces waters inland, causing silty sediments to find temporary repose across riverbanks, floodplains, and shorelines. The different stages between the trembling of the ground, and a tidal wave rising is a period where fractures and fissures develop, a time of fearful memory according to Charles Darwin, who experienced the 1835 earthquake along the Chilean coast. Darwin recounted the effect with the kind of logical detachment associated with his voyages: “First, at the instant of the shock, the water swells high up on the beach with a gentle motion, and then as quietly retreats; secondly, sometime afterwards, the whole body of the sea retires from the coast, and then returns in waves of overwhelming force. The first movement seems to be an immediate consequence of the earthquake affecting differently a fluid and a solid, so that their respective levels are slightly deranged: but the second case is a far more important phenomenon.”

Although the word estuary is a noun, it can be translated to aestuarium in Latin, which comes from aestus—an opening. The associa- tion with estuary as an action or occurrence indicates that “estuary” might be reconfigured as a verb. If so, then the 2010 tsunami estuaried the coastline, mudflats, islands, and the town of Constitución.

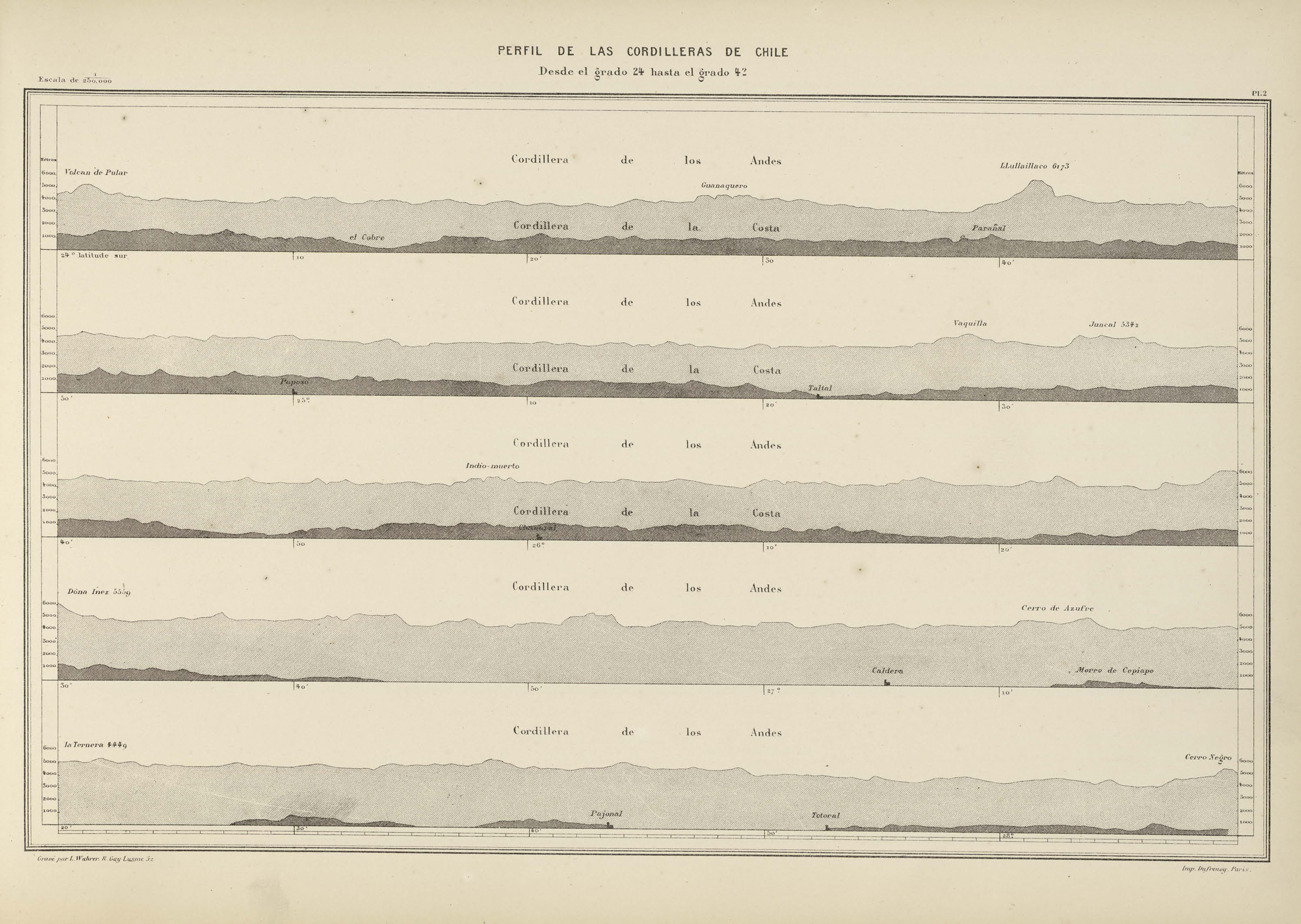

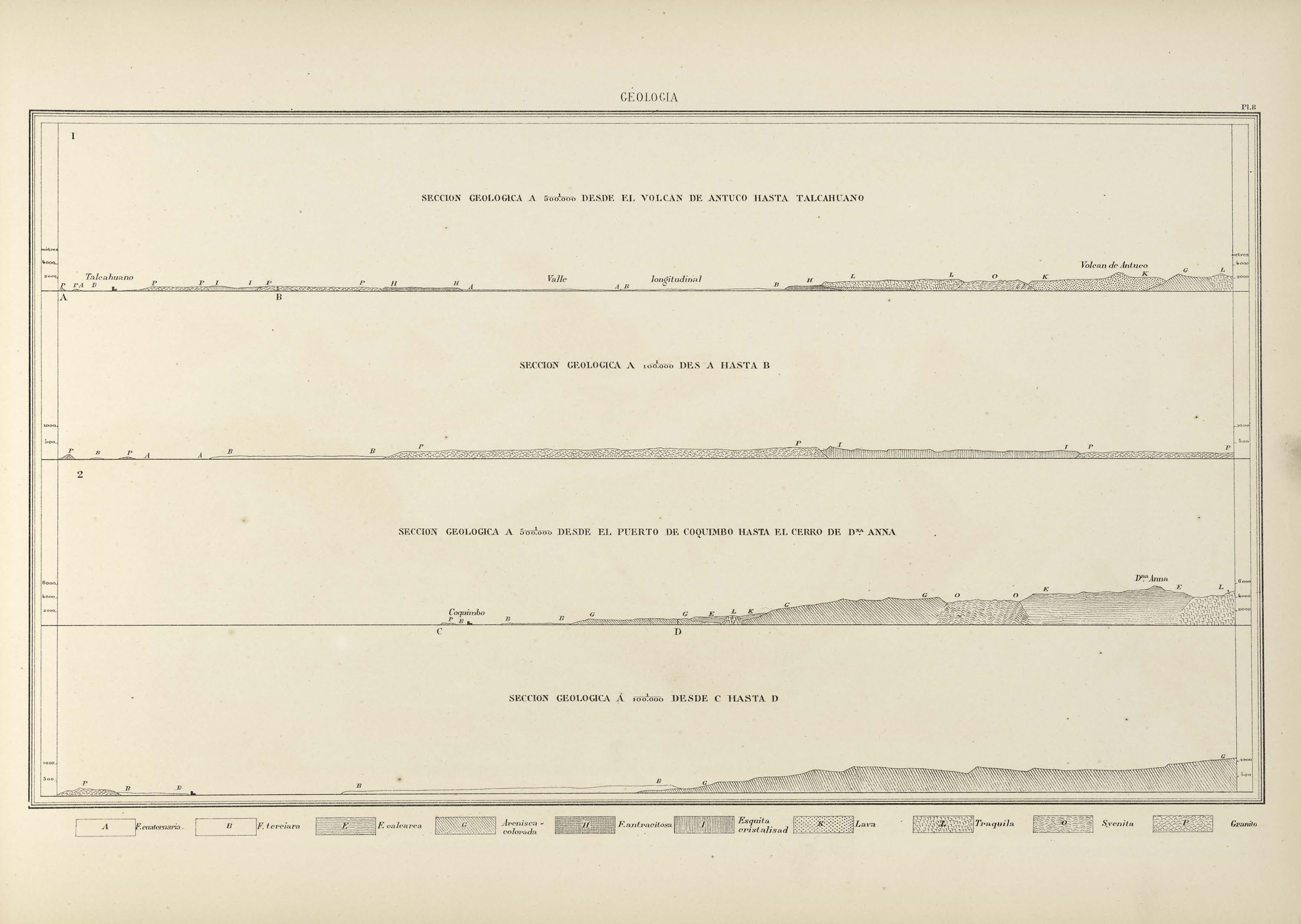

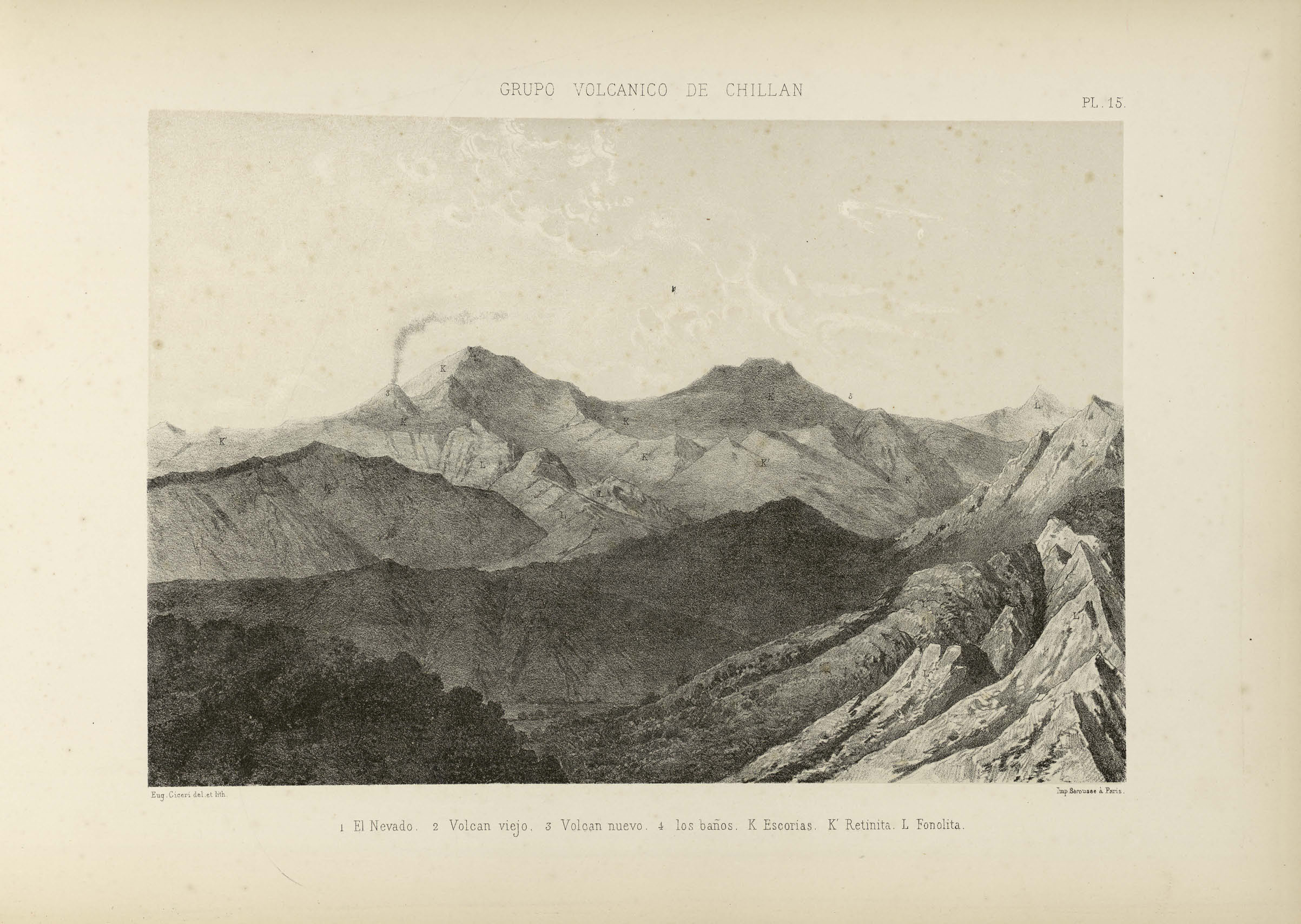

The dynamic formation that estuaries a setting is analyzed by geologists in layers, lateral deposits that read like tree-rings set deep into the shoreline. But tsunamis do not form rings, they deposit lateral marine sands in thick bands. Each layer chronicles tsunami events. The thickness of marine sand sheets also validates historic record, unwritten or otherwise oral accounts by providing material evidence of each event. The “event beds” near Constitución can be read as far back as 1575 and include major events in 1835 and 1960. Such deep analysis is the territory of paleo-studies, associating the present with a past that confirms estuarine behavior. In the present, the issue is contoured by policy, by risk-assessment that arises from earthquake prone areas. The tsunami actions that estuary the coast are not presnt in the measures associated with current risk. This translates to a community prepared for earthquakes, but negligent of tsunamis. The endless formation of the southwest coast of Chile is a region activated by tectonics and scientists, an experience that congregates around geologic diversity in charts, tables, and monitoring. The dynamic formations that estuary the coast are hidden from the human community, obscured by a century of industrial activity.

On 20 February 1835, Charles Darwin was in the forest above Concepción, and he describes the after-effects of the earthquake and tsunami once he reached the shores and spoke with his fellow travelers. Of particular interest is the difference between these two experiences:

2

Charles Darwin, Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle round the world (London: John Murray, 1876), 519.

The return of the whole body of the sea depicts the approach as ocean waters encounter coastal geology, rushing upstream with irresistible force, often physically transforming the shoreline by raising the elevation with its silty deposits. Wherever coastal or riverine geology is made up of hardened infrastructure, the force meets seawalls, foundations, and embankments that destroy estuarine subtleties and replace the possibility of physical reconfiguration with the reality of destruction.Although the word estuary is a noun, it can be translated to aestuarium in Latin, which comes from aestus—an opening. The associa- tion with estuary as an action or occurrence indicates that “estuary” might be reconfigured as a verb. If so, then the 2010 tsunami estuaried the coastline, mudflats, islands, and the town of Constitución.

The dynamic formation that estuaries a setting is analyzed by geologists in layers, lateral deposits that read like tree-rings set deep into the shoreline. But tsunamis do not form rings, they deposit lateral marine sands in thick bands. Each layer chronicles tsunami events. The thickness of marine sand sheets also validates historic record, unwritten or otherwise oral accounts by providing material evidence of each event. The “event beds” near Constitución can be read as far back as 1575 and include major events in 1835 and 1960. Such deep analysis is the territory of paleo-studies, associating the present with a past that confirms estuarine behavior. In the present, the issue is contoured by policy, by risk-assessment that arises from earthquake prone areas. The tsunami actions that estuary the coast are not presnt in the measures associated with current risk. This translates to a community prepared for earthquakes, but negligent of tsunamis. The endless formation of the southwest coast of Chile is a region activated by tectonics and scientists, an experience that congregates around geologic diversity in charts, tables, and monitoring. The dynamic formations that estuary the coast are hidden from the human community, obscured by a century of industrial activity.

On 20 February 1835, Charles Darwin was in the forest above Concepción, and he describes the after-effects of the earthquake and tsunami once he reached the shores and spoke with his fellow travelers. Of particular interest is the difference between these two experiences:

“A bad earthquake at once destroys our oldest associations: the earth, the very emblem of solidity, has moved beneath our feet like a thin crust over a fluid; one second of time has created in the mind a strange idea of insecurity, which hours of reflection would not have produced. In the forest, as a breeze moved the trees, I felt only the earth tremble, but saw no other effect. Captain Fitzroy and some officers were at the town during the shock, and there the scene was more striking; for although the houses, from being built of wood, did not fall, they were violently shaken, and the boards creaked and rattled together. The people rushed out of doors in the greatest alarm. It is these accompaniments that create that perfect horror of earthquakes, experienced by all who have thus seen, as well as felt, their effects. Within the forest it was a deeply interesting, but by no means an awe-exciting phenomenon.”

3

Charles Darwin, Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of the H.M.S. Beagle round the world (London: John Murray, 1876), 522.

— Charles Darwin, The Voyage of the Beagle