The Hidden Forest

Earlier in this text, I quote Anne Winston Spirn, a landscape architect and scholar who writes one of the most meaningful references for the landscape of retreat, because Spirn explicates how the loss of language conceals knowledge of other species, namely how plants leaf, flower, fruit, or set seed, how roots grab hold and how each behavior unsettles landscape as a surface. In turn, she commits to a reading of landscape created by multispecies relations and amendatory practices. In turn, it is hard not to see the landscape as a thickened space, or to experience Nijinomatsubara as a mature canopy, because the forest was actually under our feet. She writes:

“Signs of hope, signs of weathering are all around, unseen, unheard, undetected. Most people can no longer read the signs: whether they live in a floodplain, whether they are rebuilding in an urban neighborhood or planting the seeds of its destruction, whether they are protecting or polluting the water they drink, caring for or killing a tree.”

12

Spirn,

11.

11.

The stand of singular pines is trying hard to evolve into a multi-species assemblage. The scattering of seeds, the miles of fungal interactions, and the entangled roots emerge as a consortium. A brave new ecology is flourishing without our approval or assistance.

13

Peter Del Tredici, “Brave New Ecology,” Landscape Architecture 96.2 (2006): 46.

The orderly process of a steady-state community is not capable of marinating itself indefinitely. Although human maintenance appears to be the primary force keeping species in place, there are forces well beyond our reach. According to Professor Kazuo Suzuki, pines are spread all over the Northern Hemisphere, since their incipience in the Mesozoic era.

14

Kazuo Suzuki, “The Significance of Mycorrhizae in Forest Ecosystems,” Plantation Technology in Tropical Forest Science (2006): 41–52.

He also contends that over 2,000 papers have been published on pine wilt disease. Somehow, the pine wood nematode is writing a multiscalar history, laced with contingency. The original birthplace of pines was in the Bering Sea where the land was connected with Alaska and Siberia.

15

Kazuo Suzuki, “Pine Wilt Disease: A Threat to Pine Forests in Europe,” in The Pinewood Nematode, Bursaphelenchus Xylophilus, eds. Mota and Vieira (Boston: Brill, 2004), 25–30 (25).

Fast forward to the end of the Second World War, and pine wilt disease is blamed for causing the annual loss of 26 million cubic meters of timber in Japan. Initially, the disease was recognized as an epidemic in 1905 in the major port city of Nagasaki, located in southern Japan. But the activity etched by mobility, trade, and global ascendency turned WW2 into a vector that connected pine wilt disease across port cities. Subsequently, the damage increased to one million cubic meters per year. And then the nematode evolves, adapts, and gets comfortable as it finds hosts in several North American species, including Larix Spp. and Cedrus Spp., but only those American species living abroad, in Europe and across Asia. The nematode poses no threat to North American stands. The nematode redefines landscape, cuts prediction down to size and finally triumphs as a chapter in the historians’ collective DNA.

The focus of the research across Nijinomatsubara gradually shifted from questions regarding preemptive retreat toward a deeper questioning of the role of cultural perception in the design of natural, animate space. This broader concern held the key to my earlier question. The community we encountered was not concerned with the function or history of coastal forests. They took absolutely for granted that it was their responsibility to care for the forest, maintain and continue the tradition as an inheritance of this grove of magical pines. The members of the community I met spoke of the forest with a pride that could only be compared to a feeling of ownership. Yet, this was public space, owned by the state and not by any individual. In low voices, each exchange was charged with regard for the trees. Everyone has a favorite, people give the trees names, pray or meditate near them and find their way by the intimacy of suggestion offered

in their form. I was struck by the fact that everyone had stories that spanned generations, each story a way of sharing the specific character of the trees and the surrounding earth.

Climate anomalies and coastal risk aside, the town prospered because plant life was respected for providing public space, cultural memory, and a critical setback from development. The forest assemblage was not only preemptive in practice, or practical in nature. Nijinomatsubara maps adaptation in its outline, embedding retreat in the community. It takes an act of design to bring landscape to life.

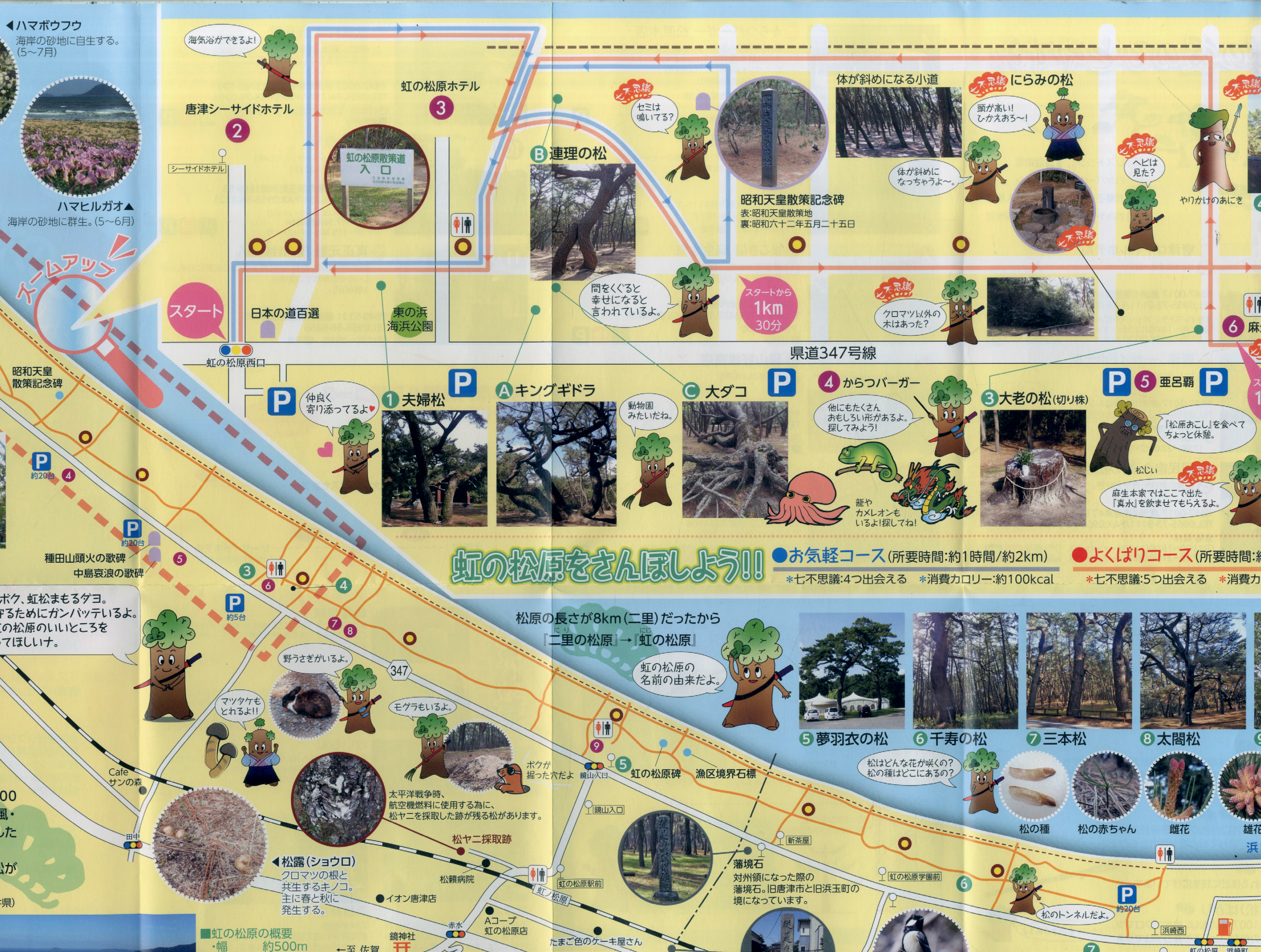

Some of the oldest and most contorted black pines are named, and adoringly used to identify paths: Big Octopus, Leaning Spear, Couple, and the Elders. Seeing plants as part of history irrevocably changes how we see and make sense of the world.

Hatsusaburo Yoshida (1884–1955) was a Japanese pictorial artist and cartographer. His approach to each site uniquely framed a depiction of landscape as not quite map and not quite guide. Rather, Yoshida used the panorama as a framing device to try and communicate time and place. Spatial transitions are blurred by train stations and routes, while attention is drawn to settlement patterns and neighborhoods that illustrate the increasing demand of tourism and its effect on the environment.

Anthropologist Eric Wolf shifts the impact of global processes from their formal outcomes to their embeddedness in local memory. Wolf's reasoning is always relative to the changeability of a culture and the multiple relations that are neither isolated nor limited by the relations between human species. Can history be contested or enhanced by plant life? Can black locust ecology change the cultural history of Japan’s tsunami forests?