NIJINOMATSUBARA FOREST

Kyushu, Japan

Japan has a long history of accepting the risks of coastal settlement. Starting in the Edo period and continuing to the present day, many communities choose to plant trees in and amongst the lands disturbed by hurricanes. In turn, these “mitigation” forests do so much more than prevent damage from blown sand, tidal surges, and salt laden wind. They provide a critical setback for development while creating a unique site of memory, uniting the community across generations. Statistics claim that only 1 percent of the Edo forests remain, and of these Nijinomatsubara is the largest and most intact of the remnant systems, surviving due to a remarkable lineage of human stewardship and care.

The Land is Ours

Nijinomatsubara is not really a forest. It feels like a forest, and it has forest-like qualities except for the fact that it is uniquely planted with black pine (Pinus thunbergii). A forest with only one species is typically called a plantation, cultivated for eventual extraction—a standing resource. But Nijinomatsubara was not planted for singular, short-term gain. The trees were planted to grow old rather than produce timber. The expanse of Nijinomatsubara stretches almost five kilometers along Karatsu Bay, an expanse of 230 hectares crossed only by a web of footpaths. Its not-quite forest, not-quite plantation status is self-stabilizing, as manifold stands are entangled by different ages, varied associations, and eventful micro-conditions. It feels like a forest because it is at once a peaceful respite for humans and a busy site of exchange for other creatures. In translation, Nijinomatsubara is also bound to a double life: it is locally labeled both a “coastal protection forest” and a “special place of scenic beauty.” It is at once productive and personal. By thwarting single categories and resisting typology, Nijinomatsubara shows us a future in which compelling ideas between human and plant life prove durable.

Ideas that include both human and plant worlds are durable when time is appreciated as an ally. Plants are temporal and social organisms, which means that they help refine landscape as an inclusive experience between species. Experience is necessarily temporal. Thus, including the temporal demands of plant life helps expand human worlds. When design is imagined for short-term benefit, the landscape suffers, and so humans and other organisms suffer. Allow me some clarification: Planting is a fiction unless it includes the extensive lifespans of the organism.

The case of Nijinomatsubara suggests that one place to look for the landscape of retreat is in the pre-history of concrete, in a time when the temporality of plant life was cherished as a legacy for future generations. Each tree was planted as a living inheritance, not installed as a built-world solution. What I found was a landscape of permanence, created by valuing the coastal shoreline beyond beaches, umbrellas, and kiosks. In turn, I can share with the reader my twent-first century pleasure experience since in this context, it strikes me that age is a helpful attribute often left out of current design mandates. Age suggests that the time associated with landscape has a particular power or capacity to deter development.

The Land is Ours

Ideas that include both human and plant worlds are durable when time is appreciated as an ally. Plants are temporal and social organisms, which means that they help refine landscape as an inclusive experience between species. Experience is necessarily temporal. Thus, including the temporal demands of plant life helps expand human worlds. When design is imagined for short-term benefit, the landscape suffers, and so humans and other organisms suffer. Allow me some clarification: Planting is a fiction unless it includes the extensive lifespans of the organism.

1

I have written elsewhere on the relationship between humankind and the act of planting, see Rosetta Sarah Elkin, Plant Life: The Entangled Politics of Afforestation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022).

Planting schemes that insist on short-term gain destroy the potential of collective experience, and any likelihood of establishing a legacy to nurture future experiences. Plant life grows and accumulates relationships with time, which means that it is likely that future generations reap the true benefit of planting design. By contrast, a concrete wall only benefits those who witness its construction. A concrete act makes inheritance irrelevant. The case of Nijinomatsubara suggests that one place to look for the landscape of retreat is in the pre-history of concrete, in a time when the temporality of plant life was cherished as a legacy for future generations. Each tree was planted as a living inheritance, not installed as a built-world solution. What I found was a landscape of permanence, created by valuing the coastal shoreline beyond beaches, umbrellas, and kiosks. In turn, I can share with the reader my twent-first century pleasure experience since in this context, it strikes me that age is a helpful attribute often left out of current design mandates. Age suggests that the time associated with landscape has a particular power or capacity to deter development.

The Maule River estuary outfalls at Constitución, one of the hardest hit communities following the tsunami in 2010. Extreme pulses of inundation are common to estuarine environments where marine sand meets river silt. At present, many estuaries along the Chilean coast are infilled by coastal concretization that intervenes between marine and terrestrial realms.

The wave action following an earthquake brought silty inundation, erosion, and deposition to the estuarine coast, a disturbance that is neither unprecedented nor particularly unique. The lineage of estuary formation across time is described by paleo-geological

analysis which confirms that the southwest coast of

Chile is a remarkably active area on

A rupture twenty-five kilometers deep beneath the Nazca plate, produced the earthquake, triggering a tsunami that traveled along the

fault at tectonic junctions. The magnitudinous waves spread beneath the coast until making landfall along the shores between Constitución and Concepción. Magnitude is relative power, and its measurement takes into account the energy released at the source. By comparison, intensity is the strength of the shaking produced by the magnitude.

The Maule River estuary outfalls at Constitución, one of the hardest hit communities following the tsunami in 2010. Extreme pulses of inundation are common to estuarine environments where marine sand meets river silt. At present, many estuaries along the Chilean coast are infilled by coastal concretization that intervenes between marine and terrestrial realms.

The wave action following an earthquake brought silty inundation, erosion, and deposition to the estuarine coast, a disturbance that is neither unprecedented nor particularly unique. The lineage of estuary formation across time is described by paleo-geological

analysis which confirms that the southwest coast of

Chile is a remarkably active area on

Above the Pines

2

The state of historic tsunami forests gained attention following the 2011 Tohoku tsunami in Sendai. See for instance: Satoshi Kusumoto et al., “Reduction Effect of Tsunami Sediment Transport by a Coastal Forest; Numerical Simulation of the 2011 Tohoku Tsunami on the Sendai Plain, Japan” Sedimentary Geology 407 (2020).

Regional risks were more likely found in the tumult and mobility of salty particulates, the typical mingling of land and water.Each protection forest was initiated to either reduce erosion, stabilize dunes, attenuate waves, limit tsunami damage, dampen salt laden wind, and prevent tidal surge, or some combination of multiple hazards. Since Karatsu was primarily an agricultural village, Nijinomatsubara was imagined by the lord of Karatsu Doman as a windbreak to shield fields from wind, sand, and salt. Yet, the breadth and limits of each planting plan did not simply depend upon the demands of the market, or the littoral morphology—it relied upon the traditions and rituals of adjacent villages. Restoration was not an embedded practice, rather, planting and its associations with growth and life were celebrated. The artificial forest is valued for its age and connections to past generations, revealing the social ties embedded in developing landscape design over the long-term.

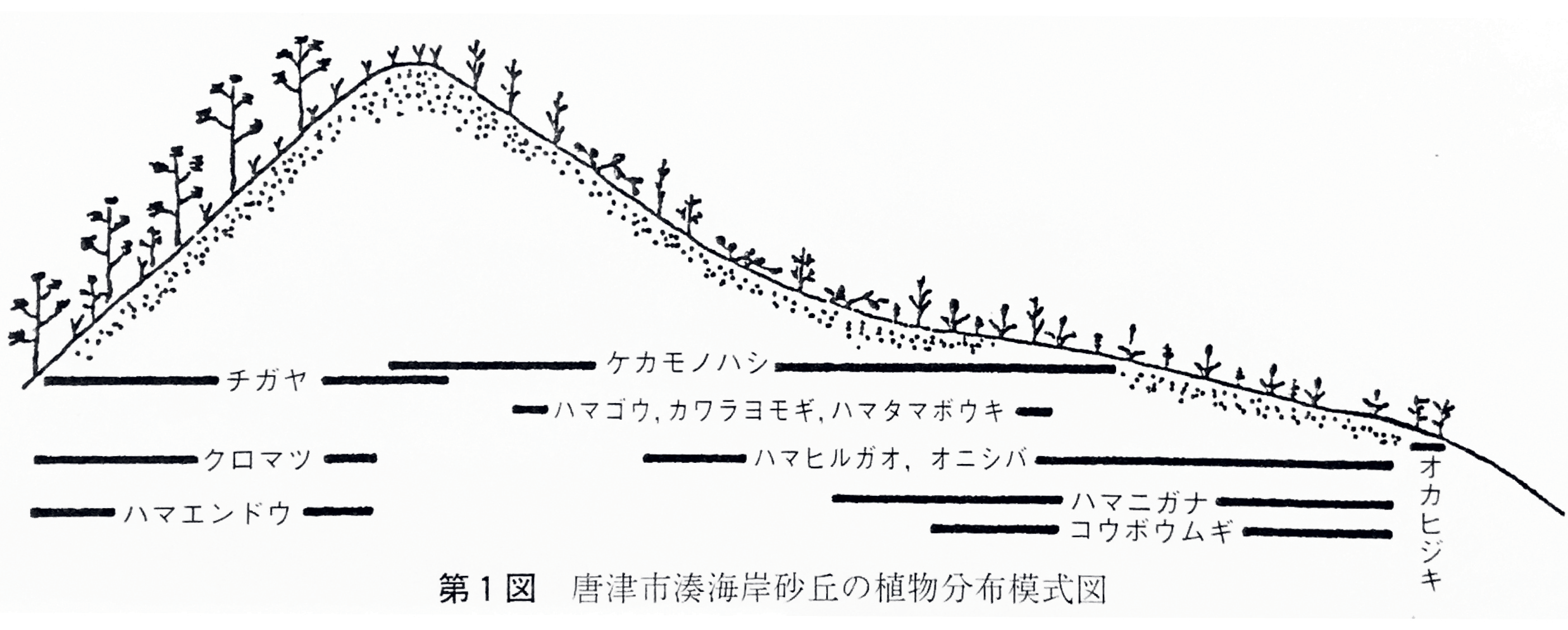

This contemporary drawing details the necessity of restoration across sand-dune communities, while ink drawings from the nineteenth century (overleaf) cultivate the meaning of a planted forest. Both type of depictions are acts of the imagination—brought to life in human, geological, and botanical time.

A rupture twenty-five kilometers deep beneath the Nazca plate, produced the earthquake, triggering a tsunami that traveled along the

fault at tectonic junctions. The magnitudinous waves spread beneath the coast until making landfall along the shores between Constitución and Concepción. Magnitude is relative power, and its measurement takes into account the energy released at the source. By comparison, intensity is the strength of the shaking produced by the magnitude.

A rupture twenty-five kilometers deep beneath the Nazca plate, produced the earthquake, triggering a tsunami that traveled along the

fault at tectonic junctions. The magnitudinous waves spread beneath the coast until making landfall along the shores between Constitución and Concepción. Magnitude is relative power, and its measurement takes into account the energy released at the source. By comparison, intensity is the strength of the shaking produced by the magnitude.

The Maule River estuary outfalls at Constitución, one of the hardest hit communities following the tsunami in 2010. Extreme pulses of inundation are common to estuarine environments where marine sand meets river silt. At present, many estuaries along the Chilean coast are infilled by coastal concretization that intervenes between marine and terrestrial realms.

The wave action following an earthquake brought silty inundation, erosion, and deposition to the estuarine coast, a disturbance that is neither unprecedented nor particularly unique. The lineage of estuary formation across time is described by paleo-geological

analysis which confirms that the southwest coast of

Chile is a remarkably active area o

The legacy of Nijinomatsubara is preserved as a story. Few accounts have ever been written and even fewer translated. In order to hear the story, I worked with landscape researcher Naoko Asano, and together we reached out to Yo Yamada, a remarkable historian who met us at Karatsu-jō, a castle that overlooks the bay and provides sweeping views of the planted forest called Nijinomatsubara. It was Yamada-sensei who suggested we start above the pines, to capture the context of legend, fable, and rumor of this magical forest. Yamada told the story in fragments, interrupted only by our enthusiastic questions and his saturated silence:

The lord of Karatsu Doman, Terasawa Shiuma-no-Kami Hirotaka (1593-1647), began planting black pine trees along the beach in 1610 because he saw that a few still remained dotted along the coast. That’s how he got the idea to plant pines. Hirotaka made sure that everyone planted trees and that no one damaged or removed any trees for firewood. He was determined to have the largest and most impressive coastal forest in Japan. He planned to forest both bays with trees and to build a castle in the center. The castle would form the head of a bird and rise elegantly towards the horizon. The forest would form the most majestic spread wings on either side of the castle.3This story was transcribed by Naoko Asano from our conversation with Yo Yamada, 12 May 2019.

This seventeenth century ink scroll painting depicts harpooning along the rocky coast and fishing from sea-borne vessels. A few pine trees mark life along the shore. Such depictions suggestively point to an appreciation and love of life along the coast.

A rupture twenty-five kilometers deep beneath the Nazca plate, produced the earthquake, triggering a tsunami that traveled along the

fault at tectonic junctions. The magnitudinous waves spread beneath the coast until making landfall along the shores between Constitución and Concepción. Magnitude is relative power, and its measurement takes into account the energy released at the source. By comparison, intensity is the strength of the shaking produced by the magnitude.

BENEATH THE FOREST?

Another Habitation is Possible

No species clings to its host quite as ardently as a fungus. They live in a dark, forbidding place somewhere in the depths of the soil, occupying a border between root and soil organisms. The fungus lives beyond notice, a footnote to fieldwork. One storm-thrashed night, the ground trembled with the wet infusion and began to move while we slept. What really captured our attention the next morning took over our plans and changed the course of the day. We were captivated by the darkly shadowed bumps around us in every direction, which, because of the way they were exposed, could be glimpsed just below the unfinished surface of the ground. Our gaze moved swiftly from the plants over our heads to the needled forest floor, our sensory imagination clouded by the allure of the delicate undulation. Naoko and I fell to our knees. Skimming the surface with our fingers created contact and the learned language of mushrooms appeared. I knew what we were observing: the entire pine forest was connected underground by a fungal network, but the name, the features, and any species recognition was absent. It didn’t matter. The very day we were present was the day the mushrooms emerged such that during a handful of hours these unnamed organisms slowly allowed their soil borne moisture to evaporate, and with every exhalation of wetness, the soil around it cooled, pushing the fruiting body further into the atmosphere, aboveground. In a kind of multispecies breathing exercise, the fungus began to sprout out and emerge all around us, translating itself from a soil inhabitant to an earth dweller, claiming a home in Nijinomatsubara.